Sites Associated with James McCune Smith and Family in New York City #4

Seeking Lavinia Smith

Dear readers, let me first apologize for not having published a new piece for so long. I had urgent family matters to attend to and had to put work and writing aside for a while. To show my appreciation for your patience, I’ve made the previous entry for this newsletter available to all subscribers.

When I left the former site of the African Free School, I picked up the pace: afternoon was about to give way to evening and the light would soon be too low for photography. I headed east and further back in time, in search of sites in the Lower East Side of Manhattan where James McCune Smith’s mother Lavinia may have lived.

As is the case with so many people born into slavery, it’s hard to find details about Lavinia’s life, especially her early life. Her brief obituaries indicate that she was born about 1783.[1] While the New-York Daily Tribune obituary describes her as ‘a native of Georgetown, S. C.’, McCune Smith later referred to Charleston, South Carolina as ‘her home.’[2] His longtime friend and editor Robert Hamilton also referred to Charleston as Lavinia’s town of origin in the biography he wrote for McCune Smith.[3] By 1855, according to the New York State census for that year, Lavinia had lived in New York City for fifty years, indicating that she arrived there around 1805.[4]

It’s hard to tell how Lavinia left slavery and why she went to New York. The two may have been connected. McCune Smith left us only tantalizing hints; though a prolific author, he tended throughout his life to be private about his family, sharing small details and anecdotes now and again. His description of Lavinia as ‘self-emancipated’ suggests that she left slavery of her own accord.[5] When McCune Smith wrote that he was ‘the son of a slave, owing my liberty to the emancipation act of the State of New-York,’ he also indicated that she was not legally free at the time she left slavery, therefore potentially passing that legal status to her son.[6] It’s possible that Lavinia left South Carolina on her own, perhaps in company with (an)other(s), and fled to relatively free New York City. Or, Lavinia may have been brought to New York City by her legal owner and took that opportunity to leave. McCune Smith’s goddaughter Maritcha Lyons wrote over a hundred years later that Lavinia was a ‘slave who had been given her freedom to make her eligible to testify in a court of justice,’[7] but I have thus far been unable to find a legal case involving Lavinia. More on some of these possibilities later.

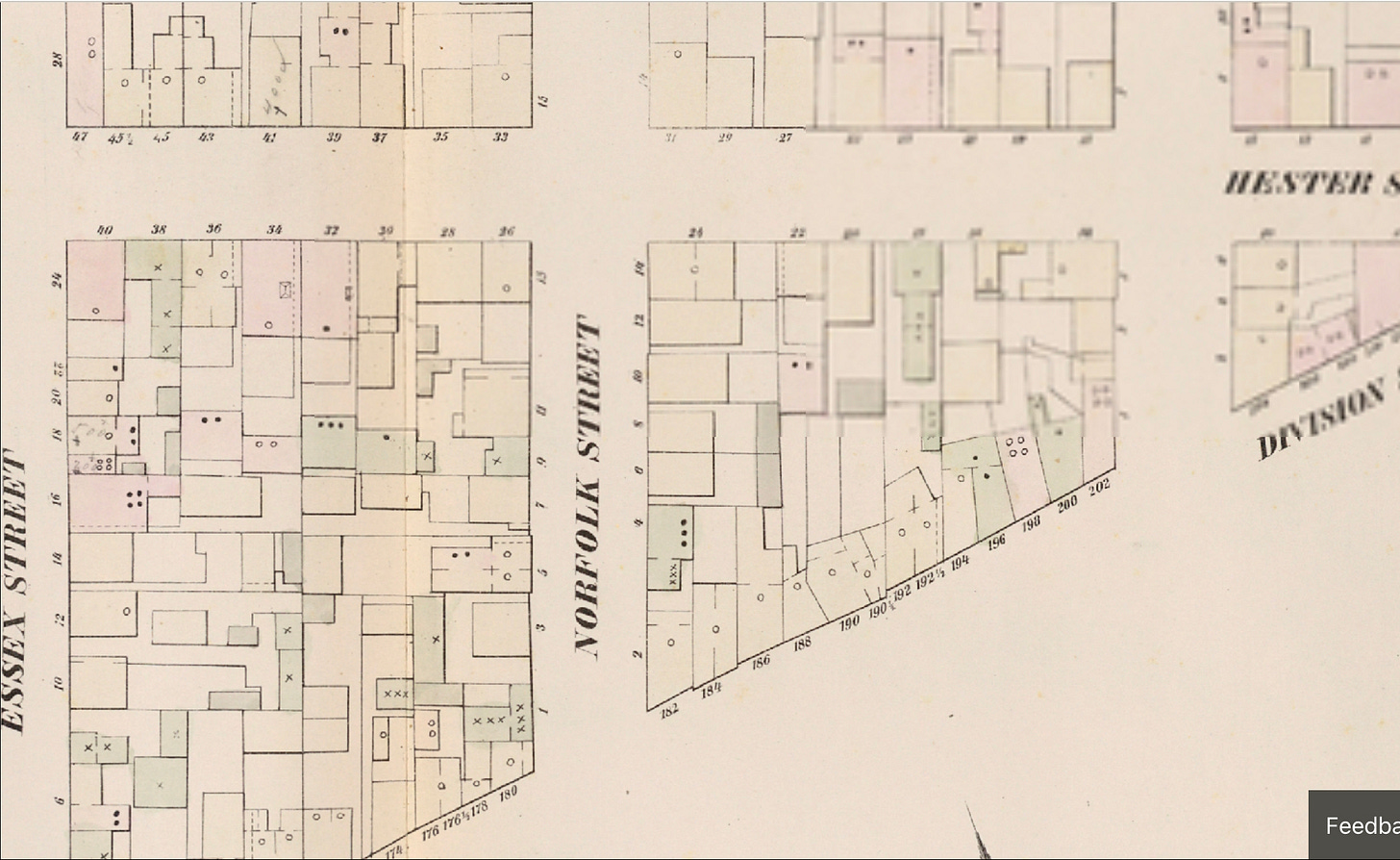

Back to my quest to find sites associated with Lavinia’s earlier years in New York City: After I walked from the African Free School site through Chinatown toward the Lower East Side, I came to the place where Hester Street now ends, but used to continue along the north side of what is now Seward Park. (See opening photo above.) Part of it still exists as a wide walkway, closed off by a coded security gate. A kind resident, after I explained what I was doing, let me through the gate so I could get as close to the first site I’m seeking: where Lavinia may have lived in 1811. A New York City directory for that year lists a ‘Smith widow Lavinia, tailor Hester n. Norfolk.’[8] This is the first directory listing I’ve been able to find for a Lavinia Smith in New York City starting in the early 1800’s.

As we can see below, the place where Lavinia Smith lived at Hester and Norfolk has been paved over and covered with a huge complex of flats and its surrounding gardens.

Now, a good question to ask, and one I’ve asked myself many times, is ‘How can we be sure that this directory listing refers to our Lavinia Smith?’ The question needs to be asked because, as it turns out, Lavinia Smith was not a terribly uncommon name, though it was not the most common either. I found women of that same name in various cities and states throughout the 1800’s. For example, there was a Lavinia Smith who was a member of a prominent family in New York State, who gave birth to a son in 1830 that would become a successful New York City merchant.[9] However, there was only one entry for a person named Lavinia Smith (with occasional variations in the spelling of the first name) in any given New York City directory in relevant years up until the late 1820’s, and never again until over a year after our Lavinia Smith’s death. Some entries for ‘Lavinia Smith’ I have been able to confirm as referring to our Lavinia by cross-referencing with other sources, as we shall see.

Our Lavinia does disappear from New York City directories after 1829. This is likely, at first, for similar reasons she was only intermittently listed before. Later on, it’s likely because she probably moved into McCune Smith’s household immediately once he returned home to New York City in 1837. The directories listed only heads of households, so Lavinia would no longer be listed once she lived in the household of her adult son. (US censuses only started listing all individual members of households in 1850 and New York State followed suit in their 1855 census; starting in those years, we find Lavinia listed in McCune Smith’s household in every census taken during the rest of her life.) I did, intriguingly, find an entry in Ancestry.com for a Lavinia Smith admitted into an almshouse from 1829-1835,[10] but have not yet managed to confirm that data entry in the original digitized sources.[11] (They’re vast and mostly not alphabetized.) However, given that there’s evidence that Lavinia made a decent living on her own and that she and her son had lots of community support,[12] I doubt that this refers to our Lavinia either.

So, returning to that 1811 directory listing: if it refers to our Lavinia Smith, which I think is more likely than not, it’s also intriguing that she is listed as a widow two years before McCune Smith’s birth. It she was a widow in 1811, she doesn’t appear to have ever remarried, since her last name remained Smith for the rest of her life. Therefore, it appears that Lavinia became pregnant with and gave birth to McCune Smith while unmarried. This may help explain the mystery of his paternity; no-one has yet been successfully identified as McCune Smith’s father, and McCune Smith himself indicated that he did not know who his father was.[13] Perhaps Lavinia did not want to acknowledge a father for her son if he did not plan to be present for him; or, perhaps the father did not want to acknowledge Lavinia and their son; or there might be other reasons for this silence in the historical record.

The next two sites I seek, which follow on in space – but not in time – are also somewhere under this sprawling complex and its grounds. One is where ‘widow’ Lavinia Smith lived in 1825 at 25 Norfolk; the other is where a Lavinia Smith, ‘tailoress,’ lived in 1827 at 20 Norfolk. The second of these entries is especially interesting, since it indicates what our Lavinia likely did for a living. If so, she seems to have been at least somewhat successful, since McCune Smith’s longtime friend and editor Robert Hamilton described the ‘means’ by which she supported herself and her son ‘ever ample and abundant.’[14]

To reach the next site, which used to be at 1 Hester Street, I retrace my steps back to Essex St, walk north, turn right on Grand, then south on Clinton St. All of what used to be Hester St runs under that Grand St complex and its sister complex at 200 East Broadway. 1 Hester St is where an 1812 New York City directory locates a Lavinia Smith, identifying her as both a widow and a tailor. The site was about where the garden is now which runs along the side of the 200 Broadway Street block of flats, on the side facing Clinton Street, which you can see in the photo below.

Since the light was very low at this point, the next site would be my last for the day. It was little more than a few steps away, under the large garden at the corner of Clinton Street and E Broadway bordered by a semicircular path. In Lavinia’s day, Division St used to run parallel to E Broadway all the way to Grand St; now, it stops at Ludlow St, west of Seward Park. So, I can only approximately locate the place where an 1815 New York City directory lists Lavinia Smith at 203 Division St, this time simply as a widow.[15]

These directory listings for ‘Lavinia Smith’ on the east side of Manhattan are all ones that I have not been able to cross-reference with other sources; the ones that I have been able to cross-reference were in and around the Five Points neighborhood. I’ll explore those with you in a future post. As you’ll see, the Five Points and more broadly the Sixth Ward were the areas most closely associated with McCune Smith’s life and his and his mother’s community; hence, the ability to cross-reference directory listings from there with other sources. This gives rise to another question which may cast doubt on the idea that these Lower East Side listings refer to our Lavinia Smith. After all, directories from 1820 and 1822 place her in the Five Points. So why would our Lavinia live in the Lower East Side for many years, then move to the Five Points, move back to the Lower East Side, then back to the Five Points again? Well, it could be that the widowed Lavinia had set up a successful tailoring business once she settled in the Lower East Side, moved to the Five Points due to other connections she had there, only to return to the Lower East Side because her business had done better there. We may never know – Lavinia left no account of her life behind, directories and public records provide only a few details, and her family and friends have only left us snippets from her story. So, the best we can do is gather little scraps from every place we can find them, and unfortunately, from these years, almost all we have is those New York City directories.

There is one exciting exception, which I’ll also discuss when we follow Lavinia Smith back in time to the Five Points. Stay tuned!

[1] ‘Death of an Aged Lady’, The Anglo-African, 24 January 1863; ‘Died: Smith’, New-York Daily Tribune, 21 January 1863.

[2] James McCune Smith, ‘From Our New York Correspondent [1, 8, and 9 December 1854]’, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, 15 December 1854.

[3] Robert Hamilton, ‘Dr. James McCune Smith’, The Anglo-African 5, no. 13 (9 December 1865): 2.

[4] 1855 New York State Census, New York County, New York, digital image s.v. “James McCune Smith.” FamilySearch.org.

[5] Frederick Douglass and James McCune Smith, My Bondage and My Freedom... With an Introduction by Dr. James M’Cune Smith (New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1855), xxxi.

[6] James McCune Smith, ‘Freedom and Slavery for Africans’, New-York Daily Tribune, 20 January 1844.

[7] Maritcha Remond Lyons, ‘Memories of Yesterdays: All of Which I Saw and Part of Which I Was - An Autobiography’ (New York, 1929), 77, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

[8] David Longworth, Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, and City Directory (New York: David Longworth, 1811), 272.

[9] Lyman Horace Weeks, Prominent Families of New York, Being an Account in Biographical Form of Individuals and Families Distinguished as Representatives of the Social, Professional and Civic Life of New York City (New York: The Historical Company, 1897), 476; ‘Lavinia Smith Riker (1796-1875) - Find a Grave...’, accessed 2 August 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/16587930/lavinia-riker.

[10] ‘Lavinia Smith, Admission, 1829-1835 in New York, New York, U.S., Almshouse Ledgers, 1758-1952’, Genealogy, Ancestry.co.uk, accessed 2 August 2023, https://www.ancestry.co.uk/discoveryui-content/view/867182:62048.

[11] Nathalie Belkin, ‘Guide to the Almshouse Ledgers, 1758-1952’, 2016, https://www.nyc.gov/assets/records/pdf/Almshouse_REC0008_MASTER.pdf.

[12] Amy M. Cools, ‘The Life and Work of Dr. James McCune Smith (1813-1865)’ (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2021), 18–19, https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/38333.

[13] Cools, 10–11, 17.

[14] Hamilton, ‘Dr. James McCune Smith’.

[15] David Longworth, Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, and City Directory (New York: David Longworth, 1815), 290.