Sites Associated with James McCune Smith and Family in New York City #3

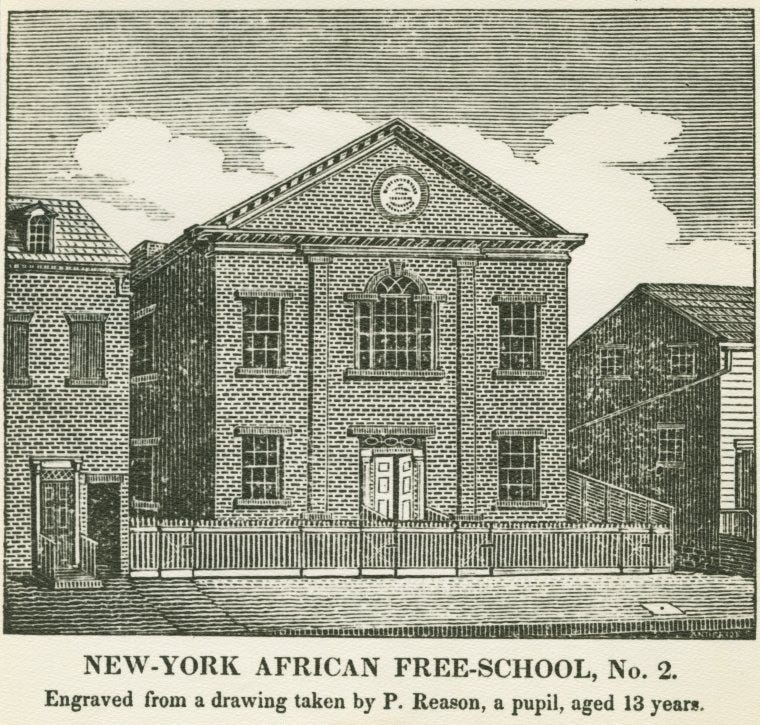

The African Free School

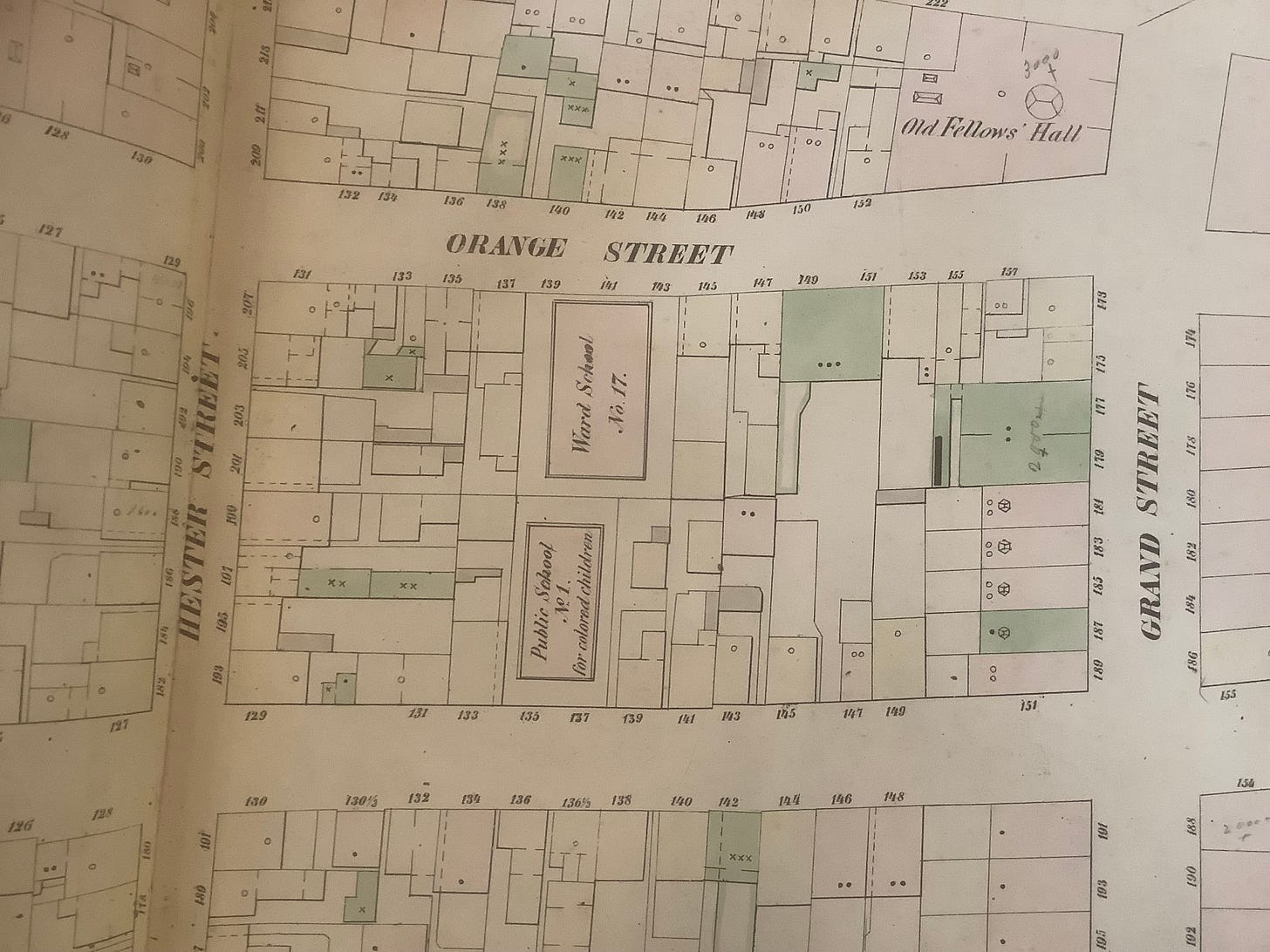

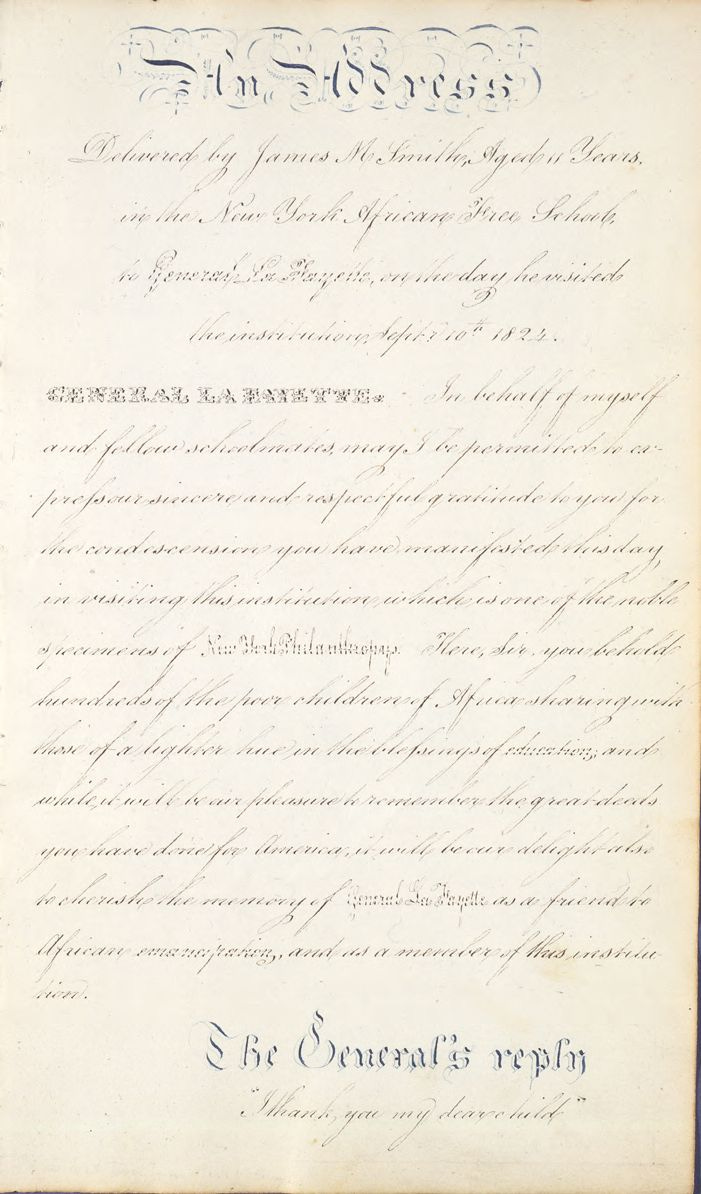

The third site associated with the life of James McCune Smith that I visited while on my recent New York City research trip (see my previous post) was where the African Free School on Mulberry Street had been. It’s unknown just when McCune Smith first started attending the School; the first contempory record of his attendance is from 1822, when McCune Smith was about eight or nine years old. It’s ‘A Dialogue: Spoken by Jas. M. Smith and William Hill at a Public Exam in 1822. Written for the Occasion by C.C.A Teacher’, in Addresses and Pieces Spoken at Examinations, 1818-1826, preserved in the New-York African Free School Records held by the New-York Historical Society. It’s a dialogue between two boys about how one of their parents doesn’t get him his breakfast early enough to be on time for school, in part because, having not been educated themselves, they don’t really understand its value. The dialogue goes on to discuss how some parents don’t support their kids well enough in their education and that sometimes, often without knowing it, those parents give their kids bad examples, leading to some kids playing truant and otherwise not behaving properly in school or elsewhere. McCune Smith’s character (under his own name, James) concludes with his hope that parents would do better in supporting their children’s education, but that teachers will also be understanding when children are absent or late through no fault of their own.[1] McCune Smith was among those lucky children who did receive full support in their educational endeavours, as we’ll continue to see, both from his loving mother Lavinia and from many others in his close-knit community. McCune Smith graduated from the African Free School by exam in the autumn of 1827.

The African Free School was founded by the New-York Manumission Society in 1787.[2] The Manumission Society had been founded two years earlier by illustrious New Yorkers; its earliest members included Founding Fathers George Clinton, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay.[3] According to the first history of the African Free School, the Manumission Society was motivated by ‘commiseration [with] the poor African slave’ and dedicated to ‘exerting all lawful means to ameliorate his sufferings, and ultimately to free him from bondage.’ This included ‘car[ing for] the children of this injured and long degraded race.’ The Society believed that ‘imparting to [these children] the benefits of such an education, as seemed best calculated to fit them for the enjoyment and right understanding of their future privileges, and relative duties, when they should become free men and citizens.’[4] Not all members, however, believed that African Americans could or should enjoy full and equal benefits of freedom and citizenship, at least not right away. As historian Leslie M. Harris writes, ‘Many of the Society’s early members included slaveowners who ‘believed that black people needed inculcation in the ways of American society, and that slavery, under the proper master, was one way of doing so.’[5] Like many early abolitionists, they thought that gradual emancipation was the only way to end slavery effectively and permanently.

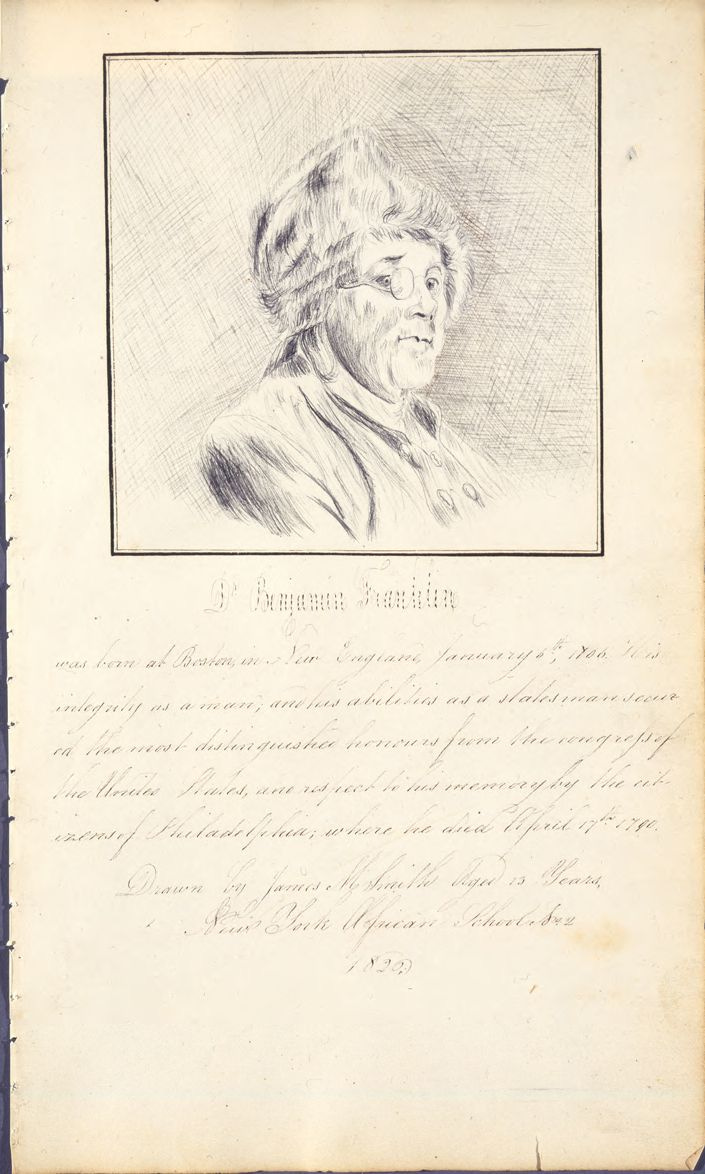

Robert Hamilton, a lifelong friend whose journalistic endeavors almost always included McCune Smith in a key role, later recalled that this ‘public school in Mulberry st., established by the Manumission Society… was a good school for those times, but not what the public schools of the city are now, or what that same school is now.’ Nevertheless, Hamilton wrote of the generation of African Free School students that included McCune Smith: ‘A more energetic class of pupils few schools ever had than were the associates of the Doctor; and few have ever, as a class, done themselves more credit through life than a majority of those have done.’[7] Whatever the shortcomings of the School in those years, it seems more than an accident that so many of its attendees and graduates went on to become some of the most talented and accomplished African Americans in history, including the activists and clergymen Henry Highland Garnet and Alexander Crummell, the great Shakespearean actor and tragedian Ira Aldridge, the Reason brothers Charles (a brilliant educator) and Patrick (an eminent engraver), pioneering newspaperman Philip A. Bell, and McCune Smith.

McCune Smith appears to have considered the illustriousness of so many African Free School graduates as not accidental at all. He credited the School with doing much to shape the character of its students. He wrote, ‘In all cases, the school-house, and school-boy days, settle the permanent characteristics, establish the level, gauge the relative, mental, and moral power of the man in after life…’[8] McCune Smith apparently thought of the School’s headmaster – who also wrote the first history of the school – as playing a key role in helping to form the character and ability of its students, even if, as Hamilton hinted, the School was not necessarily top-notch. Over four decades after he began to attend the School, McCune Smith recalled that

African School, No. 2, was then taught by Mr. Charles C. Andrews, an Englishman by birth, of versatile talents; himself not deeply learned, but thorough so far as he went, a good disciplinarian, and in true sympathy with his scholars in their desire to advance. One special habit of his was to find out the bent of his boys, and then, by encouragement, instruction, and, if need were, employing at his own expense additional teachers to develop [sic] such talent as far as possible.[9]

Rather than criticizing Andrews for his limitations, McCune Smith gave him credit for recognizing them, to the benefit of his students. He recalled that Andrews ‘hired more competent teachers at his own expense’ so that those in advanced classes could get the most out of them.[10] In sum, McCune Smith appears to have credited Andrews’ influence more to how intensely he cared about his students and their success than to how brilliant a scholar he was.

As we’ve seen, McCune Smith’s attendance at the African Free School is first attested in a dialogue he and another student participated in for a public exam in 1822. Some contemporary scholars look askance at the practice of exhibiting students in such a way as exploitative and or even dehumanizing. For example, Anna Mae Duane analogizes this practice to displaying children as if they were ‘specimens.’[11] However, McCune Smith did not see it that way. Rather, he regarded Andrews’ use of that practice as a way of showing his pride and confidence in his students’ abilities, as well as a way to instill a greater sense of confidence and the drive to excel within them while providing them with opportunities to earn rewards for their efforts:

In spelling, penmanship, grammar, geography, and astronomy, he rightly boasted that his boys were equal, if not superior, to any like number of scholars in the city, and freely challenged competition at his Annual Examinations. …To stimulate his pupils, and bring out their varied talents, he instituted periodical fairs, at which were exhibited the handiwork of the children, who were rewarded by tickets and those creature comforts which schoolboys and girls so well know how to estimate.[12]

Throughout his years promoting, fundraising, and serving the Colored Orphan Asylum as a physician, McCune Smith himself regularly presided over such exhibitions of the children’s scholarly skills.

It seems that McCune Smith even regarded Andrews as a key influence in making his African American students believe in their own equal worth and capabilities in a society that mostly sought to deny these, despite the fact that Andrews apparently held the same gradualist views of ending slavery that many members of the Manumission Society held. Prior to naming fellow graduates of the African Free School who went on to achieve great things, McCune Smith wrote:

Without being, in the modern sense, an abolitionist, Mr. Andrews held that his pupils had as much capacity to acquire knowledge as any other children, they were the object of his constant labors, and it was thought by some, that he even regarded his black boys as a little smarter than whites. He taught his boys and girls to look upward; to believe themselves capable of accomplishing as much as any others could, and to regard the higher walks of life as within their reach.[13]

But not all McCune Smith’s friends and fellow students at the African Free School remembered Andrews so fondly. Almost two decades before McCune Smith wrote the biographical sketch of his old friend and fellow African Free School student Henry Highland Garnet, from which the above quotes are taken, Garnet had written a short biographical sketch of McCune Smith. In it, Garnet recalled that ‘Mr. Andrews, like Master Busby, believed most religiously in the use of the rod, and if the subject of this article [McCune Smith] escaped the application of this popular mode of sharpening the youthful intellect, he was more fortunate than many of his fellows.’[15]

But it was probably less a matter of good fortune and more a matter of McCune Smith’s being an exemplary student; indeed, Garnet praised McCune Smith on this account in the sentence that follows the above quote. And when Andrews suffered a near-fatal illness in 1827 which forced him to stay home for well over two months, he had already appointed McCune Smith to serve as ‘monitor general.’ As such, he was responsible for helping to oversee the education of younger students and to maintain order in the classroom. While Andrews was ill, McCune Smith found himself entrusted with the far greater responsibility, at only thirteen years old, of largely filling in for Andrews. Though McCune Smith struggled at times to maintain discipline among the unruliest students, the trustees of the School who stopped by every few days to check on things were well satisfied with his performance.[16]

In any case, McCune Smith appears to have considered what Garnet called a ‘popular mode of sharpening the youthful intellect’ as less of a problem than he did. Perhaps McCune Smith saw it as merely a relic of an earlier time, and therefore didn’t blame those who had struck children with canes or rods for disciplinary purposes back in Andrews’ day. Or, perhaps McCune Smith regarded it as a legitimate or even wholesome method of punishment in certain circumstances. (Either one of these views may have been much easier to hold if you were not among those who regularly ended up on the wrong end of the cane.) As the New York correspondent for Frederick Douglass’ Paper in 1852, McCune Smith wrote what he evidently considered a humorous anecdote of such a punishment being delivered to his lifelong friend Philip Bell. He recalled,

One of us, (now, Phil, I shan't say who,) had "played hookey," (truant,) and came to school duly prepared, by extra pantaloons, to undergo the usual flagellation; which would have passed on very well, had it not been for an unfortunate layer of paper, which betrayed an unusual sound to Charley Andrew's quick ear, and the rattan went wop! Stripping off the extra garment, Charley laid on with a mischievous vigor which brought from the boy a hundred exclamations of Oh! Oh! Oh! Mr. Andrews, I'll never! Oh! Mr. Andrews, and finally, "dear Mr. Andrews! my dear Mr. Andrews!" which brought down the house; even Charley Andrews could cut no more, neither can I.[17]

In the end, Andrews’ tendency to quickly resort to corporal punishment, however common it was at the time, did not sit well with many students, parents, and others associated with the African Free School. Alumni Alexander Crummell and Albro Lyons (another close friend of McCune Smith’s) recalled this tendency with strong disapproval. Eventually, in 1832, Andrews was fired, principally for this very reason.[18] But regardless of all the controversy surrounding Andrews, it appears clear that McCune Smith himself was still inspired by the strict but comprehensive methods of his old teacher for the rest of his life.

…As I review this piece for publication, I surprised myself at the degree to which Charles Andrews and his legacy ended up playing in it. It was really supposed to be mostly about the African Free School overall and McCune Smith’s experiences there. But this also reminds me of one of the purposes of this newsletter. As I work on McCune Smith’s biography, I’m working out historical puzzles such as the one I ended up puzzling over in this essay: how is it that so many students of such a controversial teacher of at least somewhat limited scholarly abilities go on to reach such intellectual heights? Why is it that one of the most brilliant of Andrews’ students, McCune Smith, recalled him so fondly when many others did not? It was McCune Smith’s own reminisces about the African Free School, in fact, that kept leading me back to Andrews. While others – such as the scholars I cite – have considered these questions, I felt like it needed a closer look, and still does. For example, how did attitudes towards corporal punishment change between McCune Smith’s primary school days and the mid-nineteenth century? Did they differ between African American communities, many of which included members that had experienced such punishments under slavery – making them that much more humiliating – and the wider society, which only experienced such punishments as free persons? In any case, I hope you find this an interesting stab at solving this particular puzzle. And don’t worry – I’ll focus much more closely on McCune Smith’s experiences at the African Free School in the book.

[1] Charles C. Andrews, ‘A Dialogue: Spoken by Jas. M. Smith and William Hill at a Public Exam in 1822. Written for the Occasion by C.C.A Teacher’, in Addresses and Pieces Spoken at Examinations, 1818-1826 (New-York African Free School Records, 1817-1832, New-York Historical Society), 45–50, accessed 1 May 2019, https://cdm16694.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15052coll5/id/28491.

[2] Charles C. Andrews, The History of the New-York African Free-Schools: From Their Establishment in 1787, to the Present Time (New York: Mahlon Day, 1830), 7.

[3] Andrews, 7–8, 10.

[4] Andrews, 7.

[5] Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 62.

[6] Thomas Longworth, Longworth’s American Almanac, New-York Register, and City Directory (New York: Thomas Longworth, 1826), 537.

[7] Robert Hamilton, ‘Dr. James McCune Smith’, The Anglo-African 5, no. 13 (9 December 1865): 2.

[8] James McCune Smith, ‘Sketch of the Life and Labors of Rev. Henry Highland Garnet’, in A Memorial Discourse; by Henry Highland Garnet, Delivered in the Hall of the House of Representatives, Washington City, D.C. on Sabbath, February 12, 1865 (Philadelphia: Joseph M. Wilson, 1865), 20.

[9] McCune Smith, 21.

[10] McCune Smith, 21.

[11] Anna Mae Duane, Educated for Freedom: The Incredible Story of Two Fugitive Schoolboys Who Grew Up to Change a Nation (New York: New York University Press, 2020), 82.

[12] McCune Smith, ‘Sketch’, 21–22.

[13] McCune Smith, 22.

[14] Andrews, History, 60–61.

[15] Henry Highland Garnet, ‘James McCune Smith, M. D. - Number II [From the National Watchman]’, Emancipator, 15 September 1847.

[16] Amy M. Cools, ‘The Life and Work of Dr. James McCune Smith (1813-1865)’ (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2021), 21–22, https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/38333.

[17] James McCune Smith, ‘Letter from Communipaw [6 March 1852]’, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, 18 March 1852.

[18] Harris, Shadow, 134–35; Carla L. Peterson, Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 78.