Sites Associated with James McCune Smith and Family in New York City #1

The Colored Orphan Asylum

As I wrote in my previous post, I recently spent two weeks in New York City, mostly in Manhattan, on an intensive research trip for the James McCune Smith biography I’m writing. One of my projects was to map out the sites associated with his life and with those closest to him. I also wanted to see what these sites look like now. So, when the archives were closed, I grabbed a few hours here and there to run around New York City and visited these sites in person.

It was a warm spring day in April when I visited the Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division in the Stephen A. Schwarzman building of the New York Public Library, at the east end of Bryant Park. It’s a beautiful room. The Map Division has digitized most of their maps, so I’ve done some research in them online, mostly among the fire insurance and property maps. However, I’ve long found that there’s just no substitute for speaking in person with archivists who know their collections inside and out and have helped many people consult them. As usual, I received great advice and suggestions that I may never have encountered, however many emails were exchanged or links clicked on.

It's also easier, and far more enjoyable, to look at the physical maps and lay them out so that the drawn streets lay out in the same direction as the real ones they’re portraying, in the same city you’re in. I know the city just well enough to have a fair idea of how the places relate to one another spatially. For each site I had an address or place description of, I consulted the maps, mostly from the 1850’s and early 60’s. that best matched the relevant time period that also had the street numbers marked out. (Most earlier maps don’t have the street address numbers marked out or building names except for major landmarks.) While a few street names and numbering remained the same, quite a few streets had been renamed, and most had been renumbered. Then I compared what I found in those old maps to Google maps and marked what seemed like the closest spot. None of the original buildings exist for any of these sites, but that’s exactly what I expected. New York City is a restless, vibrant, ever-changing place, and has been built and torn down and rebuilt almost entirely many, many times. But the old building for today’s site, as you’ll see, is no longer there for another reason.

Given that it was a warm lovely day, I decided to take advantage of it and start visiting the McCune Smith-related sites I had mapped out right away. My other work I had to get done would just have to wait – at this time of year, when there’s sun to be gotten, you go get it. The first site, which we’ll consider today, was right around the corner.

This was the site of the Colored Orphan Asylum, where McCune Smith was the attending physician for almost two decades. The Asylum was founded in the autumn of 1836 by Anna Shotwell and Mary Murray, two Quaker women with strong anti-slavery beliefs who were dismayed that New York City’s existing orphan asylum excluded all non-white children.[1] McCune Smith had long been associated with the Asylum by the time he was hired for the post of head physician, perhaps first becoming intensely interested in its mission through his mentor Peter Williams, Jr, who had played an important role in its foundation. McCune Smith regularly donated medical services for the children and fundraised for them.[2] One of his most well-known works, 1841’s ‘A Lecture on the Haytien Revolutions; With a Sketch of the Character of Toussaint L'Ouverture,’ was delivered and published to raise funds for the Asylum.[3] By the time McCune Smith was appointed head physician in 1846, he had affirmed the Asylum’s managers’ realization that the growing institution, if it was to fulfill its mission as well as possible, needed a permanent medical staff and a hospital. He was instrumental in getting the latter funded and built.[4] It opened its doors on 26 June 1850. McCune Smith wrote in his physicians’ report for that year that the ‘ample’ new addition with its ‘sunny side, a quiet school-room, and a mild teacher’ was so popular with the children that healthy ones tried to get McCune Smith to admit them.[5]

There are some lovely anecdotes of the Asylum and McCune Smith that survives in a memoir of Thomas Barnes – called ‘Tommy’ by his friends and playmates[6] – who lived there with his brother after his parents died. The Barnes family were connected to McCune Smith by familial relations to his close friends. The Asylum accepted them in 1860 upon McCune Smith’s recommendation.[7] Tommy described the Asylum as a welcoming place, with two to three hundred children curious and excited to meet him and his brother. Tommy was impressed by its being ‘fully equipped with modern conveniences… There was hot and cold running water on every floor and thorough ventilation. In the basement were spacious play rooms for boys and girls separate, bathrooms with eight large tubs, twice the ordinary size, two plunge baths, and swimming pools.’[8] He remembered McCune Smith as ‘a man of medium height and rather corpulent [with] a fine head, lofty brow, quick dazzling eyes.’ As a physician, Tommy remembered, he was kind, taking special care of him and his brother, but would not put up with any nonsense.

I must relate an incident to illustrate one of Dr. Smith’s methods. During the winter of ’61 and 62’ I had an attack of sore throat and was sent to the hospital but soon recovered. There was a school for convalescence in the hospital, presided over by a miss Robinson, a young colored woman. She was a very pleasant and agreeable teacher. The school curriculum was simple, consisting principally of story reading by the teacher and drawing pictures on the black board by the pupils, all of which I enjoyed immensely. The doctor, in making his rounds, pronounced me well and ordered me back to regular school. I protested, stating that I was not well. The doctor very curtly replied to the nurse, “Give Thomas a dose of cod liver oil every night and morning. Perhaps he will prefer that to school.” I took the oil. …It was the old fat, thick, crude cod liver oil, administered with a big iron spoon with a short handle, deep, narrow bowl and a sharp wedge-shaped point made to pry open the patient's mouth to force the dose. About the time the second dose was administered, I concluded I was well and went back to school.’[9]

Tommy’s anecdote reveals that at least some children were still faking illness so they could stay in McCune Smith’s pleasant hospital many years later.

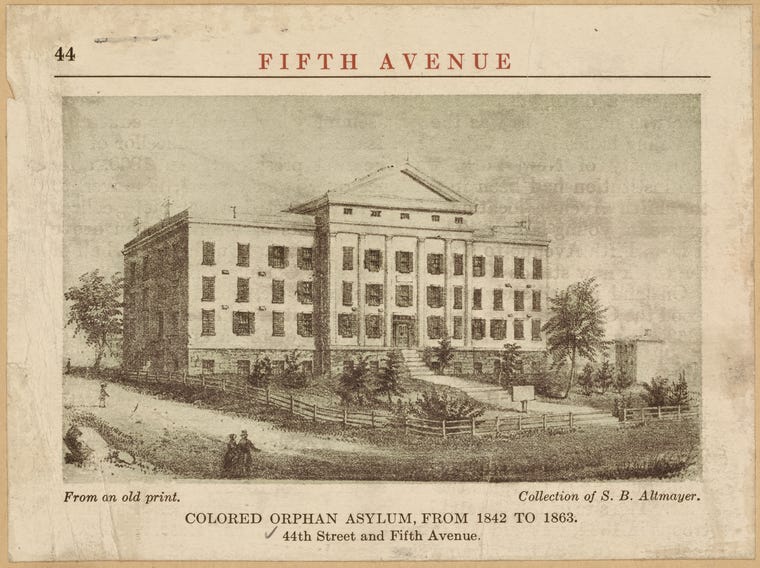

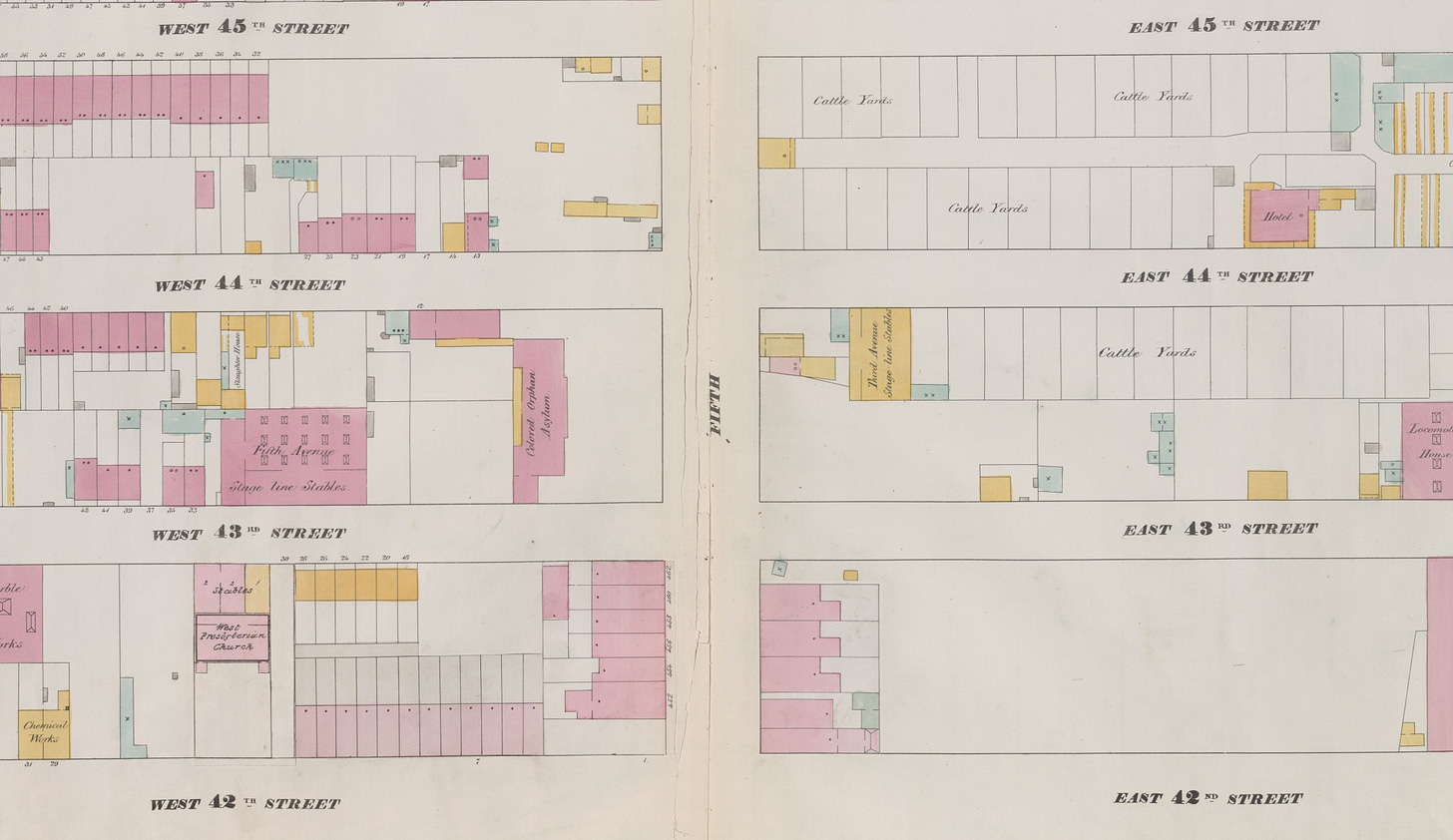

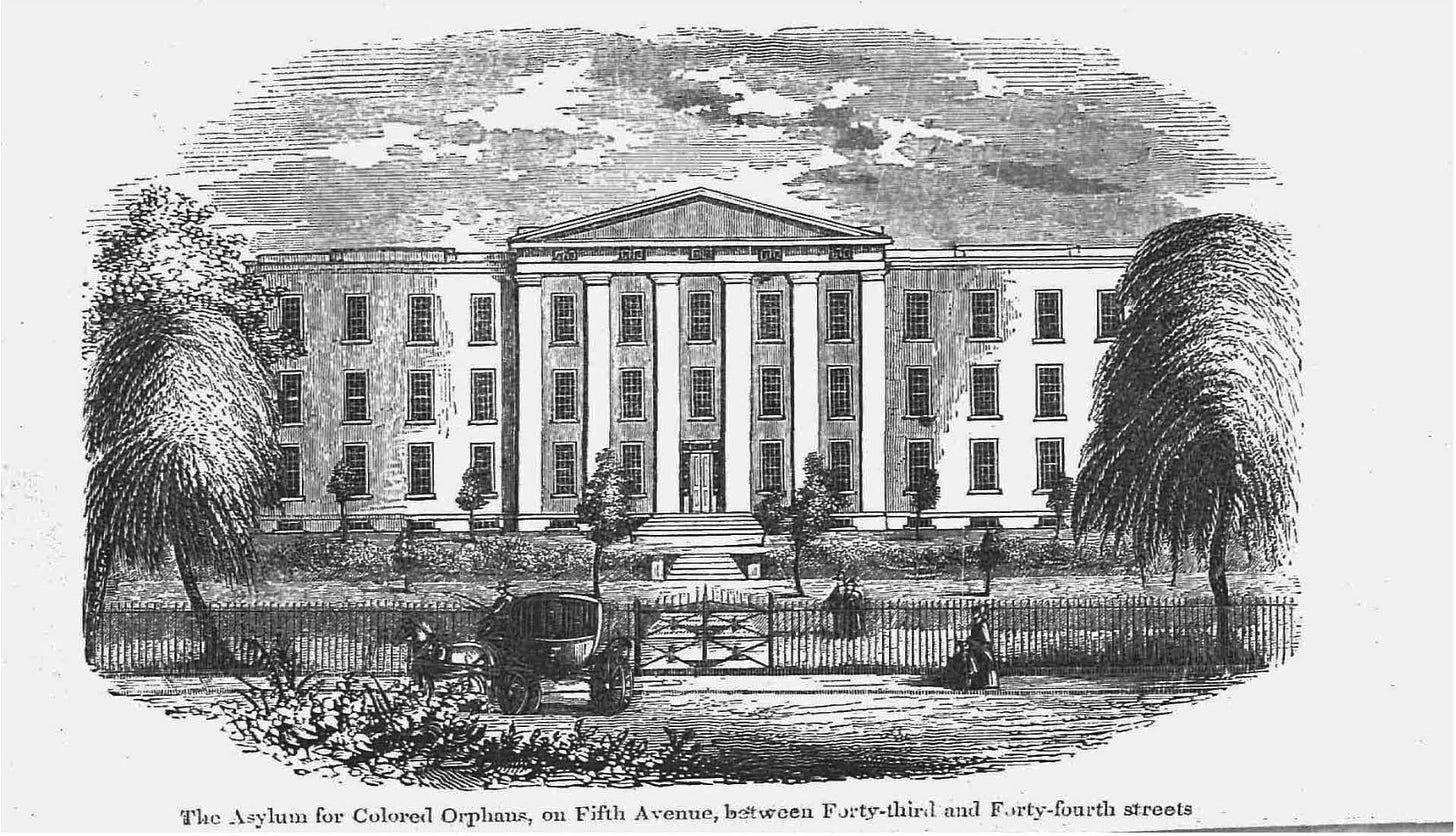

As you can see from the detail of the 1859 William Perris map above, the Colored Orphan Asylum was huge. (Look for the large building, shaded pink and labeled ‘Colored Orphan Asylum,’ at the center left.) It stretched for nearly a whole block on Fifth Avenue, between West 43rd and West 44th Streets. Indeed, directories and other sources of the time don’t provide an address for the Asylum – it didn’t need one. They just describe its location in terms like these: ‘Fifth Avenue, between Forty-third and Forty-fourth streets.’[11] By 1846, as pictured in the Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphan’s Tenth Annual Report, it was already imposing, with a large classical pediment supported by columns in its central portion, and large wings on either side. The addition of the hospital would have made it even more so.

As those of you who know New York City well, 43rd Street is not particularly close to lower Manhattan, where McCune Smith lived at the time that he proposed the building of the hospital after many years of providing free consultations. This distance proved to be a problem. In 1847, a correspondent to the National Era wrote that McCune Smith was ‘actually denied the use of the cars [on the Harlem railroad], after his friends had procured him a free ticket, to enable him to visit on professional business the Colored Orphan Asylum.’ He was denied admission to the train, of course, on account of race.[12] In New York City, like in so many American cities, the public transportation operators routinely segregated whole trains, segregated cars within the trains, or just left it up to conductors to decide whether they’d admit African American passengers as they wished.[13] It would have been a real inconvenience, to say the least, for McCune Smith not to be able to freely take the train, besides the horrible insult to his humanity. According to Google Maps, it’s an hour’s walk from where McCune Smith lived at the time (15 North Moore Street, which we’ll consider in a future post) and where the Colored Orphan Asylum was. And while I haven’t looked closely at the cost of hiring private intra-city transportation at the time, I imagine it would have been quite a bit more expensive than taking the train – and he probably would have encountered racial bigotry in trying to hire that kind of conveyance as well. In 1853, McCune Smith and fellow leading African Americans Thomas Jennings and James W. C. Pennington founded an organization called the Legal Rights Association (LRA) dedicated to combat segregation on public transportation in New York City. It was the violent ejection of Jennings’ daughter Elizabeth from a railroad car that immediately inspired the founding of the LRA, but it seems clear to me that McCune Smith also had his own and others’ like experiences in mind as well when he immersed himself in that cause. It was successful, though only after a decade of legal wrangling – by 1864, all New York City railroad lines were desegregated.[14]

As I stepped out of the cool low light of the Maps room and the Schwarzman building into the bright warm sunshine, the massive differences in the appearance of this part of New York City then and now struck me with even more force. Peering into old maps, I was taken back to a time when this part of Manhattan had lots of space. As you can see from the map, it was enough for sprawling cattleyards, stables for the horse-drawn railcars, and a chronically underfunded orphan asylum to have a sprawling institution here with gardens and playgrounds. This is decidedly no longer the case. As you can see, the sidewalk is teeming with people and Fifth Avenue with cars and buses, with new construction going up in this already jam-packed site. It’s so hard to picture the graceful, classical structure set well back from the road, surrounded by trees, that used to be here.

As all this bustle and construction reminds us, and as we’ve considered already, New York City has always been a metropolis that’s constantly torn down and rebuilt and added on to. With a relatively few exceptions and mostly not until the mid-twentieth century, it was not a priority to preserve beautiful or historically significant structures if they could be torn down and built over with more profitable or more fashionable or fancier ones instead. We will never know if the Colored Orphan Asylum would have been one of those rare examples of an old building preserved for its beauty, because it was valued by the community, or for any other reason.

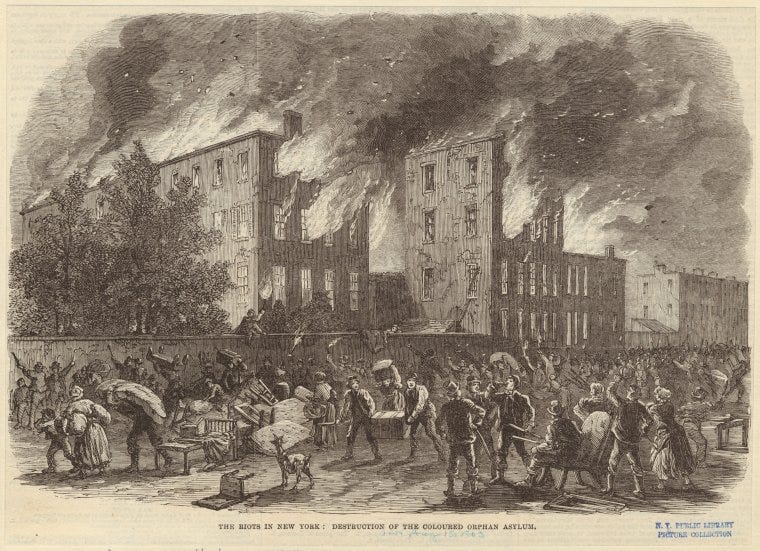

That’s because, on 13 July 1863, it was trashed, looted, and burned to the ground during the New York City Draft Riots. It started as a working-class protest against a draft law enacted at a time when the Civil War was going badly for the North. Among other things, this law conscripted men by a lottery system into the Union army unless they could pay a $300 fee to the government or pay someone to enlist in their stead. These were options most people could not afford, and there was widespread anger at the idea that the wealthy could get out of fighting while the poor were forced to go to war. The protest quickly evolved into five days of violent rioting, in which government and military buildings and African Americans – who many blamed as the cause of the war – were the primary targets.[15]

It is shocking to us, and indeed it was shocking to most then, that anyone would steal from and then burn down an orphan asylum, whatever the race of the inhabitants or however prevalent racial prejudice was. Even newspapers that tended to promote racist and anti-abolitionist views, such as the New York Herald and the New York Times, published lots of commentary on the destruction of the Colored Orphan Asylum expressing disgust, anger, or at least disapproval.[16] Apart from the natural personal reaction they might have against the thought of innocent children being attacked and made homeless, these articles also suggest to me that the editors felt that the public would also blame them for their years of inflaming racial hatred in their newspapers. So, they gave plenty of space in their pages for righteous indignation against the outrages committed by the violent mob.

On that terrible day, Dr James Parker Barnett, not McCune Smith, was in attendance when the rioters descended on the Asylum, at about four in the afternoon. Barnett was McCune Smith’s brother-in-law, his wife Malvina’s youngest brother.[17] According to Anna Shotwell, Secretary of the association that ran the Asylum, ‘The Physician in attendance, Dr Barnett, had through the day of the mob felt great anxiety as to the safety of the Institution. He was carefully watching, and gave the first alarm.’[18] As he wrote in his annual Physician’s Report in December of that year, McCune Smith noted that while he had been ‘Prevented by severe illness, for the larger portion of the year, from visiting the Asylum, the undersigned bears grateful testimony to the assiduous care, ready skill, and affectionate attention which was paid to the children by Dr. James P. Barnett, now temporarily engaged as acting-assistant surgeon in the army.’[19] Fortunately, all the children survived the riots, as I have written elsewhere, ‘saved by staff, sympathetic bystanders, and police officers of the 20th Precinct house.’[20] Tommy Barnes, recounting the chaos and cruelty of the scene that day, also recalled that ‘O’Brien, chief of the fire department, was killed on the front steps [of the Asylum] in his attempt to prevent the mob from entering the building’ and that for three days, the police fought to protect the children and others who took refuge in the 35th Street station house.[21]

McCune Smith could only periodically visit his beloved young patients over the remaining two years of his life due to recurrent bouts of the chronic heart condition that eventually killed him. But he continued to fundraise for them, as he had done since the time he had first come to be associated with the Asylum.[22] Young Tommy evidently didn’t hold a grudge for McCune Smith’s cod-liver oil trick. As he wrote in his memoir, ‘After four years [at the Asylum], it was my duty and pleasure to carry [McCune Smith] with horse and buggy to and from the Hudson River Railroad Station at 152nd Street. The last visit he made to the Asylum [sic] he had become old, infirm and retired from practice.’[23]

[1] Anna H. Shotwell, ‘Brief History of the Institution’, in Eighteenth Annual Report of the Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphans (New York, NY: John F. Trow, 1864), 11; William Seraile, Angels of Mercy: White Women and the History of New York’s Colored Orphan Asylum (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013), 8–9.

[2] Amy M. Cools, ‘The Life and Work of Dr. James McCune Smith (1813-1865)’ (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2021), 134–37, https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/38333.

[3] ‘A Lecture on the Haytien Revolution...’, New York Journal of Commerce, 20 February 1841; James McCune Smith, A Lecture on the Haytien Revolutions; With a Sketch of the Character of Toussaint L’Ouverture. Delivered at the Stuyvesant Institute, (For the Benefit of the Colored Orphan Asylum,) February 26, 1841 (New York: Colored Orphan Asylum, 1841).

[4] James McCune Smith, ‘Appeal. In Behalf of the Establishment of an Infirmary for Sick Colored Orphans, to Be Added to the Colored Orphan Asylum’, in Eleventh Annual Report of the Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphans (New York, 1847), 24–28; Cools, ‘Life and Work’, 136–38.

[5] Second Annual Report of the Governors of the Alms House, New York, for the Year 1850 (New York: William C. Bryant & Co., 1851), 87–88.

[6] Twenty-Eighth Annual Report of the Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphans (New York: John F. Trow, 1864), 24–25.

[7] Thomas H. Barnes, My Experience as an Inmate of the Colored Orphan Asylum, New York City (Fanny, Douglass Barnes, and Miriam Crawford, 1924), 5–7.

[8] Barnes, 7.

[9] Barnes, 12.

[10] Detail from William Perris, Plate 81: Map Bounded by West 47th Street, East 47th Street, Fourth Avenue, East 42nd Street, West 42nd Street, Sixth Avenue, image, Maps of the City of New York Surveyed Under Directions of Insurance Companies of Said City by William Perris, Civil Engineer and Surveyor, 1859. Volume 5 (New York: William Perris, 1859), New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-bf87-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

[11] David Thomas Valentine, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, for 1852 (New York: Corporation of the City of New York, 1852), 306, https://archive.org/details/manualofcorporat1852newy/page/306/mode/1up?view=theater.

[12] ‘Spectator’, ‘Letter to the Editor’, The National Era, 9 September 1847.

[13] Marcia Kirk, ‘Omnibuses and Horse Cars or What I Have Learned from Assisting Researchers’, NYC Department of Records & Information Services: For the Record (blog), 18 May 2018, https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2018/5/18/omnibuses-and-horse-cars-or-what-i-have-learned-from-assisting-researchers.

[14] Cools, ‘Life and Work’, 53–58.

[15] Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

[16] ‘The Mob Unmasked - Its Character and Spirit’, The New York Times, 24 July 1863; ‘City Government’, The New York Times, 29 July 1863; ‘The Colored Orphan Asylum - Appeal for the Honor of Old Ireland’, New York Herald, 30 July 1863.

[17] Amy M. Cools, ‘Roots: Tracing the Family History of James McCune and Malvina Barnett Smith, 1783-1937, Part 2’, Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society 37 (2020): 54.

[18] Twenty-Seventh Annual Report of the Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphans (New York: Mahlon Day & Co., 1864), 12.

[19] Twenty-Seventh Annual Report, 17.

[20] Cools, ‘Life and Work’, 57.

[21] Barnes, My Experience, 16–19.

[22] Twenty-Seventh Annual Report, 14.

[23] Barnes, My Experience, 12.

I love learning new things from your research! I didn’t know Barnett was the dr at the asylum after mccune smith or that he was a surgeon in the army! Thank you for he work you are doing. So excited to learn more!