The other day, I began another deep dive into digitized newspaper databases, especially one which I had subscribed to relatively recently. I found some exciting stuff. Among those that stood out were about lectures James McCune Smith delivered in cities outside of New York.

Now, to anyone who had read about fellow African American abolitionists and public speakers, such as Frederick Douglass or Sojourner Truth, this might not stand out. After all, many traveled all over the United States delivering their message of freedom and justice for all. But this was not true for McCune Smith. Once he returned home to New York City from Scotland, he did not often travel far from home. His pharmacy and especially his medical practice – including, starting in 1843, his work for the Colored Orphan Asylum, first as a volunteer consultant and then for nearly 20 years as attending physician – made it difficult to get away from the city very often, as he wrote to his friend Gerrit Smith.[1] On the relatively rare occasions when he did travel far afield, it was usually to attend a Colored Convention or for other anti-slavery or civil rights purpose. So, when I do come across additional sources about where and when McCune Smith traveled, and why he went there, it always stands out.

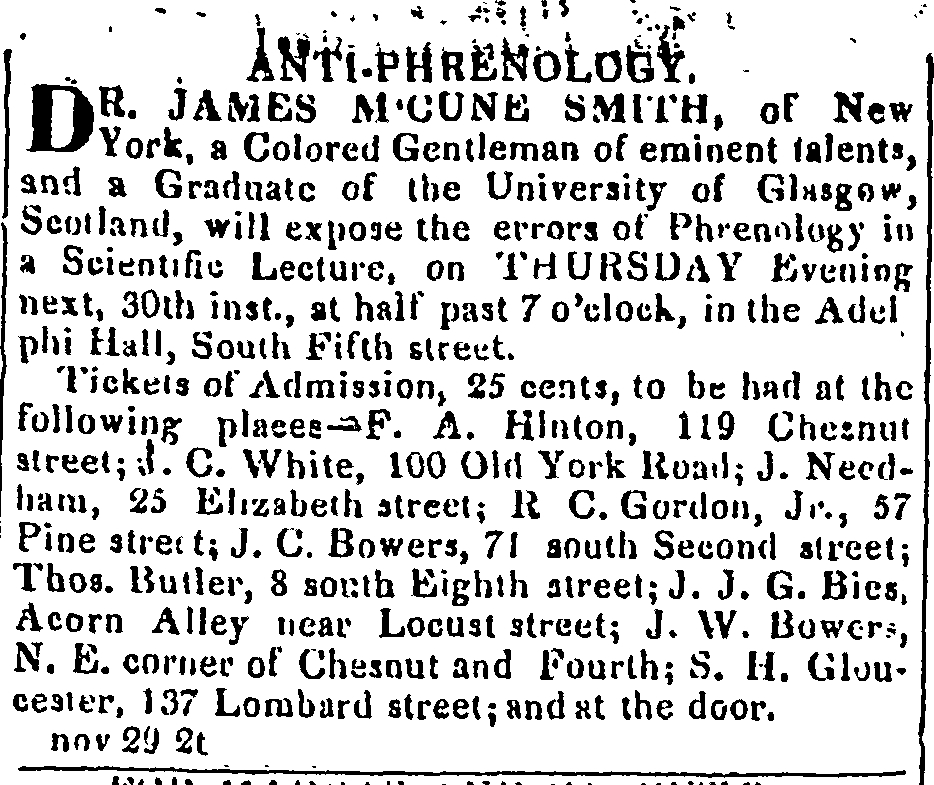

The image that opens this piece, above, is the first newspaper item related to McCune Smith’s travels that I came across the other day.

According to this notice, McCune Smith was engaged to ‘expose the errors of Phrenology in a Scientific Lecture’ in Philadelphia’s Adelphi Hall on South Fifth Street on 30 November 1837. As we can see, it describes him as a ‘Colored Gentleman of eminent talents, and a Graduate of the University of Glasgow, Scotland.[2]

Now, I had long since found a report of a lecture that McCune Smith delivered at that Philadelphia venue, but it happened early the following year, on 8 January 1838. It was on ‘the importance of classical and mathematical studies.’ The article praises it as a ‘highly creditable production;’ describes McCune Smith’s ‘through (sic) classical education at the University of Glasgow, Scotland;’ comments upon his ‘good voice, pleasing manners, and good delivery;’ and includes an excerpt (see footnote).[3]

But there had been something missing: according to an editorial by Samuel E. Cornish[4] for his paper The Colored American, a ‘Special Meeting of the Philadelphia Library Company of C.[olored] P.[eople]’ invited McCune Smith to deliver two lectures in Philadelphia. One was to be ‘on the fallacy of Phrenology, and the other on Education.’ A special committee of the Library Company, which included Cornish’s brother James Cornish, would ‘make all necessary arrangements.’[5] I hadn’t been able to find anything about that first lecture they invited him to give in Philly… until a couple days ago.

McCune Smith’s lecture against phrenology was, in fact, a continuation of a lecture tour he had embarked on almost immediately upon his return home to New York City in September 1837. Theorists and practitioners of phrenology, now considered a pseudoscience, sought to establish a science of the mind by combining psychological theories with observations of the structure of the brain. Phrenologists claimed that the brain was made up of multiple organs, each of which correlated with particular mental faculties. Since, they believed, the skull conformed to the shape of the brain during infancy, skilled phrenologists could determine one’s ‘mental character’ by observing the shape of their skull, since protuberances, depressions, and other surface peculiarities revealed the relative dominance and the interactions of the mental organs of that person’s brain. [6]

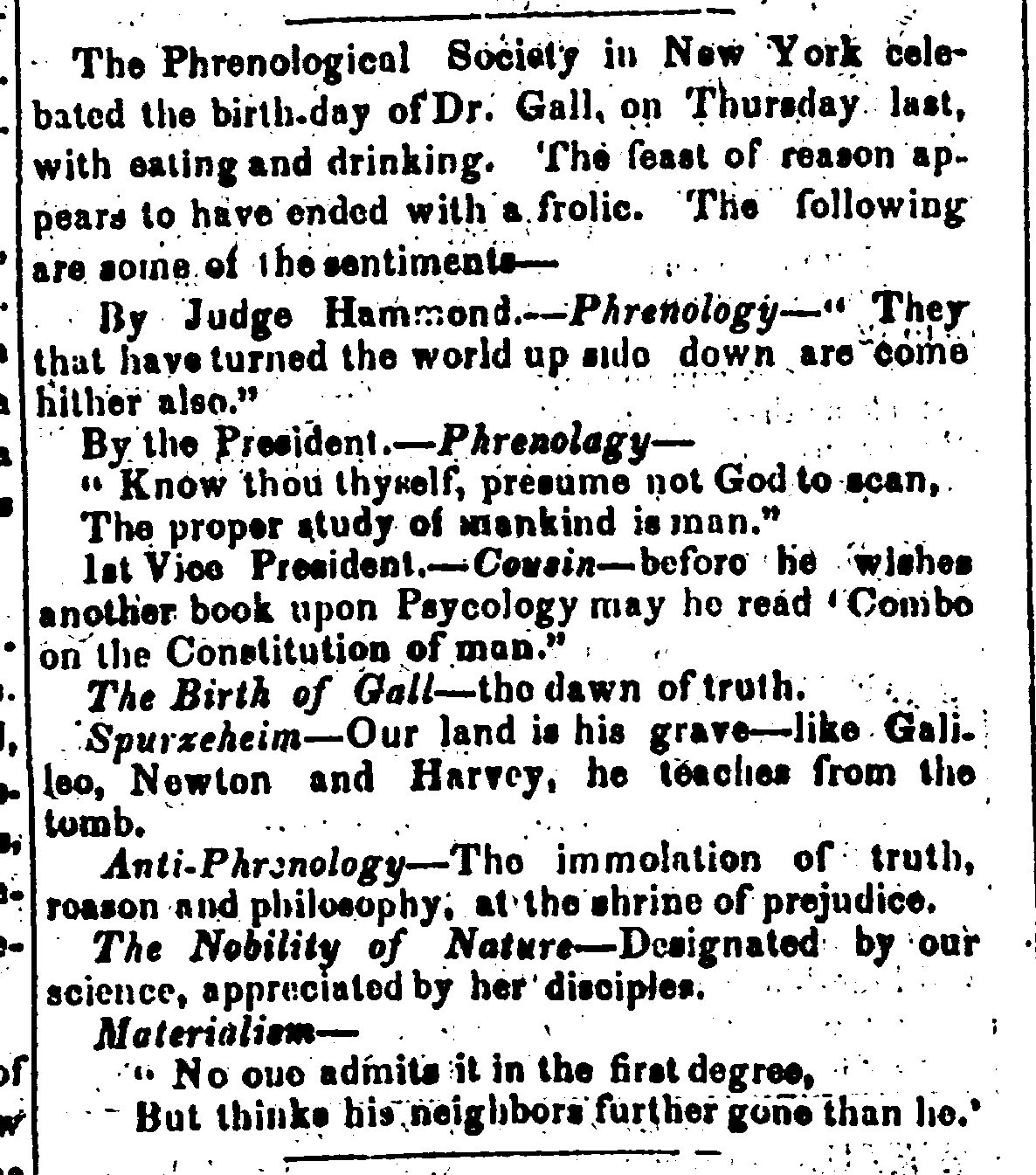

But phrenology was more than an attempt at a scientific theory. An excellent study of George Combe, a Scottish progressive social reformer and one of the most prominent advocates of phrenology, describes phrenology particularly well as ‘at once a pseudo-science, a religion, and a social philosophy.’[7] I was reminded of that again during my search for more newspaper items related to McCune Smith’s phrenology lectures, in Philly and elsewhere. Many of its enthusiasts do appear downright religious in their expressions of enthusiasm for its tenets. They were also prone to accusing skeptics and critics of prejudice. Many insisted that the ‘science’ was so obviously true that refusal to accept it must be prejudice. For example, see this brief account of a meeting of New York’s Phrenological Society, held to celebrate the birthday of Franz Joseph Gall, phrenology’s major founding theorist. The Society described ‘Anti-Phrenology’ as ‘The immolation of truth, reason and philosophy, at the shrine of prejudice.’[8] The religious imagery here, including the rather hysterical suggestion that phrenologists were martyrs to bigotry, is no coincidence.

McCune Smith almost certainly formed what phrenology enthusiasts would have described as ‘prejudice’ against it when he was still a student in Glasgow. Combe was just one of many who were very active promoting phrenology in Glasgow and throughout Britain when McCune Smith was a medical student; phrenology had plenty of prophets preaching its gospel there.[9] While there is good reason to believe McCune Smith did not attend Combe’s lecture series on phrenology in Glasgow,[10] as we shall see, he would almost certainly have been thoroughly familiar with the claims of phrenology and the intense debate surrounding it by the time he returned to the United States. After all, he started delivering his detailed lectures and demonstrations against phrenology almost immediately upon his return.

McCune Smith’s first anti-phrenology lecture – that I or anyone else, to my knowledge, has been able to find – was delivered about two weeks after he arrived in New York City. This was on 18 September 1837, at Philomathean Hall on Duane Street in NYC. According to a glowing review in New York’s Commercial Advertiser,

As a lecturer, Dr. S. possesses many points of excellence. His modest demeanor, the ease of his address, the absence of all pedantry, and the facility of his elocution, were all calculated to bespeak the favor of his audience, among whom were a number of gentlemen belonging to the several learned professions, all of whom appeared to be interested, and indeed highly gratified. - The arguments he advanced against the "science so called" denominated phrenology, were, some of them, entirely new, and all of them pertinent and forcible. By the aid of skulls, and extemporaneous drawings, upon the black board, he demonstrated the fallacy of the attempt to designate the developments of the brain, by external convexities upon the skull, when no corresponding concavities are discoverable on its internal surface. He showed the arbitrary character of the divisions of the organs, from the fact that the convolutions of the brain are in no case conformable to these divisions, and that the natural divisions of the cerebrum, by a membrane which descends between its convolutions, are altogether at variance with the artificial and imaginary separations into distinct organs which phrenology supposes.[11]

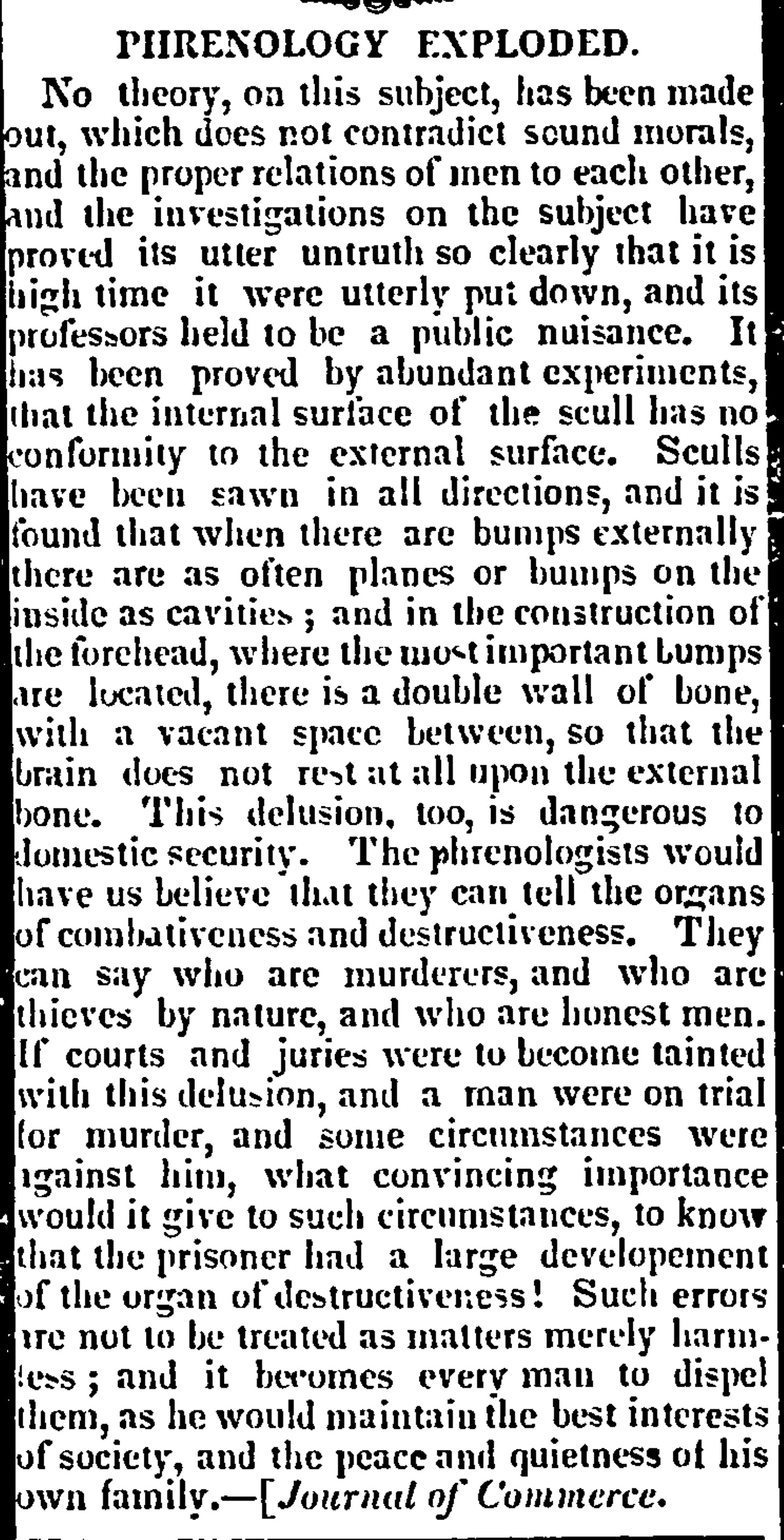

McCune Smith was far from alone in his opposition to phrenology. Many wrote to editors of newspapers deriding it with such words and phrases as ‘delusion,’ ‘humbug,’ and ‘a system of fortune-telling.’ Cornish, who reviewed McCune Smith’s 18 September lecture as glowingly as the reporter did, referred to phrenology dismissively as a system of ‘bumpification[s]’ and ‘high pretensions.’[12] Other editorials and letters also critiqued it on scientific, moral, and common-sense grounds, such as the one below, which was published and re-published in New York newspapers:

McCune Smith gave his series of lectures against phrenology when it was a really hot topic, in the United States as well as Europe. In searching in the database to see if I could find even more information on McCune Smith’s anti-phrenology lectures, limiting the results to the timeframe of mid-September 1837 and the end of June 1838, I ended up with well over 1,200 hits in just one US newspaper database alone! A huge number of the items that came up gave notice of or reviewed lectures promoting or opposing phrenology by scores of real or purported experts in various fields, in addition to editorials and letters to the editor such as I describe above and below.

McCune Smith delivered his anti-phrenology lecture again on 19 October 1837, again in New York City but this time at ‘Broadway Hall, near Howard street,’ ‘at the solicitation of several scientific gentlemen, and of numerous friends who could not gain admission at his last Lecture.’[13] The Philadelphia engagement, then, turned McCune Smith’s presentation into a de facto anti-phrenology lecture tour, even if he had initially intended it to be a one-off. His audience turned out to be much larger, and less exclusively local, then it appears he had imagined it to be.

While phrenology, if remembered at all, is now often negatively associated today with later uses of it to demonstrate a hierarchy of racial classifications, many of its early proponents were confident that it could be used to scientifically disprove claims that there were races which were mentally superior to others. The prominent abolitionist paper The Liberator republished a rather credulous (to my eyes at least) account of a prominent phrenologist who conducted a public examination of a skull that, to the reporter at least, conclusively demonstrated that phrenology was a true science. To me, the account describes something very much akin to what the aforementioned critic of phrenology dismissed as ‘fortune-telling’ – a parlor trick in which the practitioner reads the room, then delivers widely-applicable generalizations in such a way (by dressing them up in language that makes them appear specific to the individual, for example, and/or are more likely to apply to people in the audience) so as to be very convincing to those who are predisposed to be convinced. (The account is very long, so I’ll include the image of it at the very end of this piece, below the footnotes.)[14] Abolitionist Sarah Grimké was also among those who very much wanted phrenology to be a true science. She described it to a fellow abolitionist as ‘perfectly consistent with the other works of God and with enlightened reason and religion’ and argued that it had the power to prove that ‘the colored man [had] the intellect of the white.’ She, for one, was very disappointed when McCune Smith came out against it.[15]

Grimké was not the only one who was disappointed. George Combe, that prominent champion of phrenology – whose admirers included Frederick Douglass, who visited him when he was in Edinburgh in the late 1840’s[16] – was also discomfited by McCune Smith’s very public opposition to the upstart ‘science.’ In his Notes on the United States of North America, During a Phrenological Visit in 1838-39-40, in discussing the Colored American, Combe wrote, ‘ This is the title of a weekly newspaper for the use of the coloured people of the United States. …The paper of 30th March has been sent to me because it contains an attack on Phrenology, a denial of its utility, and a commendation of the philosophy of Dr Thomas Brown, and that of Mr. Young of Belfast. It is edited by Samuele [sic] Cornish and James McCune Smith. I am told that one of the editors is a coloured gentleman, who studied medicine in Edinburgh, and imbibed the prejudices of his teachers against the science, and that he is now laboring to transfer them to his colored brethren.’[17] (Combe was wrong, of course, about McCune Smith’s medical education – it was in Glasgow, not Edinburgh.) Unfortunately, the 30 March 1839 issue which would have contained McCune Smith’s anti-phrenology editorial is one of the few issues of the Colored American that I have not been able to track down. Hopefully, a copy of it will someday be found.

But Combe did not stop at expressing his disappointment. He invited McCune Smith to attend ‘his entire course of lectures on Phrenology at Stuyvesant Institute’ in New York City. In an editorial for the Colored American – for which he was then serving as co-editor – McCune Smith wrote that, due to ‘engrossing professional duties,’ he only had time to attend four of them. He thanked Combe for the free tickets, and was impressed with Combe’s ‘glorious old Scottish accent’ and his ‘skillful delineation of character which afford a rich intellectual treat.’ However, McCune Smith wrote, he ‘heard nothing from the distinguished lecturer which led us to change any of our views regarding the fallacies of Phrenology.’[18]

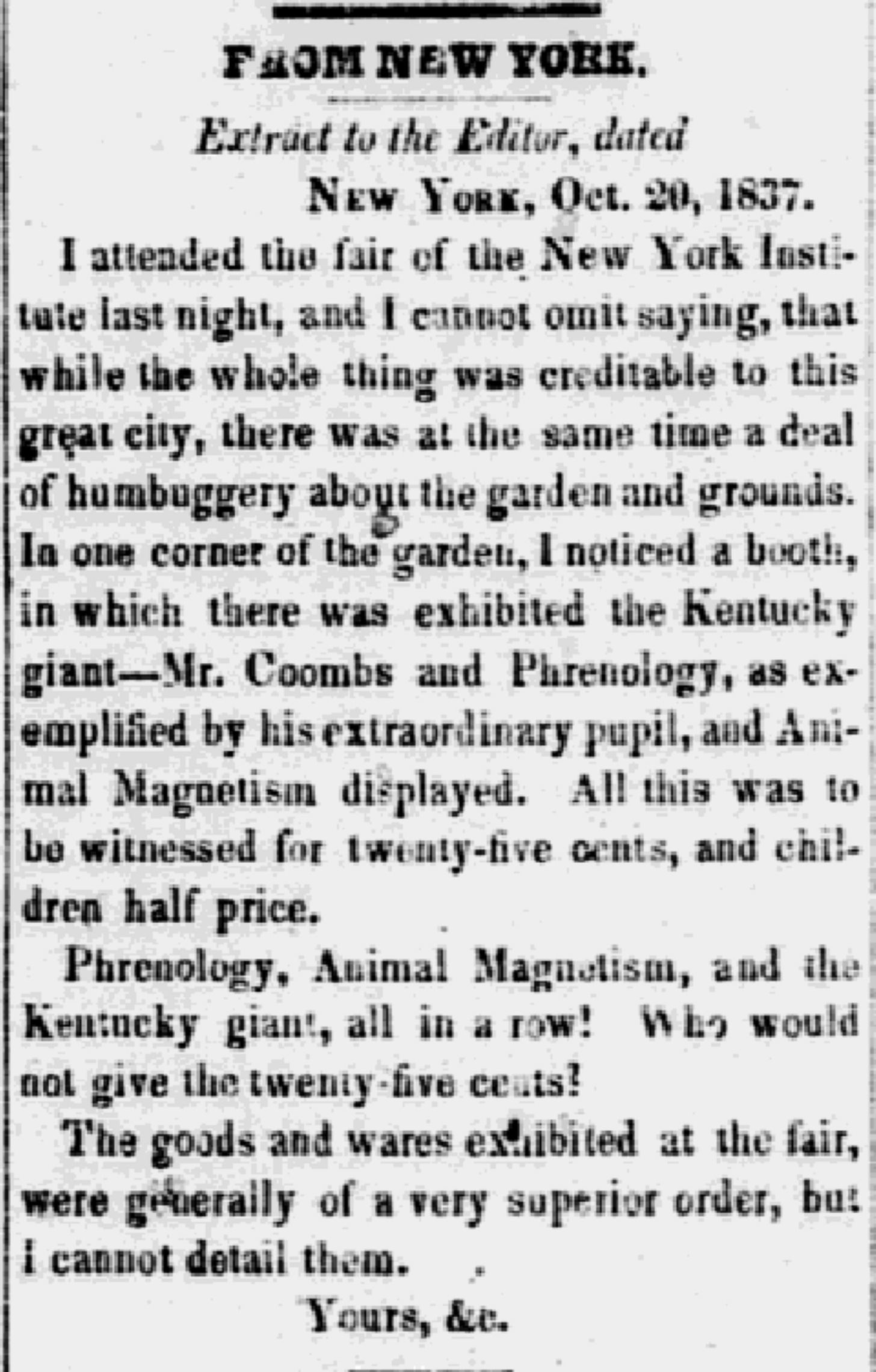

Others were similarly unimpressed with Combe’s arguments in favor of phrenology. A scathing letter to the editor from two years before lampooned Combe’s teachings on phrenology as little more than a sideshow, fittingly exhibited as mere entertainment:

There’s an interesting footnote to the story of McCune Smith and anti-phrenology. In his obituary for McCune Smith, his lifelong friend Philip A. Bell recalled: ‘In September of [1837, McCune Smith] returned to New York… Phrenology was then making considerable progress in America and the doctor gave a course of lectures in opposition to that science, although afterwards he became a partial convert.’[19] What does this mean? Did McCune Smith come to believe the science of ‘bumpification,’ as Cornish so dismissively described it – as in, that one can determine the mental characteristics of a person based on protuberances and depressions on their skull? I really don’t think so – nothing in his later writings indicates such a thing. I’m inclined to think that perhaps McCune Smith came to believe that there are distinct parts of the brain that are responsible for distinct functions, a theory that can be seen as somewhat analogous to the central claim of phrenologists. Or, perhaps Bell was just speaking of McCune Smith’s expressed respect, perhaps increased over time, for phrenologists’ close observations of different aspects of human ‘character.’

[1] James McCune Smith to Gerrit Smith, 12 May 1848, Gerrit Smith Papers, Syracuse University Libraries.

[2] ‘Anti-Phrenology’, The National Gazette and Literary Register, 30 November 1837. This notice also ran in the same paper on 29 November, and I found another almost identical ad in another Philly paper: ‘Anti-Phrenology,’ Public Ledger, 30 November 1837.

[3] ‘A Classical Scholar (From the United States Gazette)’, The Philanthropist, 16 January 1838.

Excerpt from address: ‘The most brilliant era in the British Parliament, was that in which it contained the largest number of finished scholars. Pitt, and Fox, and Sheridan, and that galaxy of genius were all of them distinguished as learned in the ancient languages, and that man who stands alone, and far above the rest, even in so distinguished an era. Edmund Burke, made the classics his study to the latest period of his life. Later still – Lord Brougham, even amid those tremendous feats of intellectual labor, which have gained for him the title of a man of iron, found leisure and necessity to cultivate the classics. And I have been told by my friend Sir Daniel Sandford, that when Lord B. was preparing that splendid peroration to his speech in defense of the Queen, he locked himself in his closet for a fortnight, constantly studying over and over again, the most powerful orations of Demosthenes, – that concerning the crown.

And in our own republic, yet young in years but brilliant in fame, the men whose names stand most prominent, and whose writings will last, are those who have been deeply imbued in the literature of the ancients. Our Jonathan Edwards, Franklin, Livingstons, Jeffersons, Adams and Everetts, are all of them the most accomplished scholars. And the man who is now the cynosure of every eye, upon whoin more than once had hung the fate of this country and the defense of her constitution, in his place in the Senate, when aggression after aggression had roused within him the lion of New-England, and at the moment when the last high-handed act filled the measure of executive encroachment, that man arose in his place, and struggling with emotion, and unable to find in our language words to express his burning thoughts, burst out in the language of his Roman prototype.

Sit denique inscriptum in omnus eujusque frontem quid de republic sentiat.

Let it be written on each man’s forehead, what his opinion is regarding the republic.

Daniel Webster is a classical scholar.’

[4] For more about Cornish, see the clipping in image 3 from a previous Substack piece ‘Our Faults – Remedies’.

[5] Samuel E. Cornish, ‘Dr. Smith in Philadelphia’, The Colored American, 23 December 1837.

[6] David De Giustino, ‘Phrenology in Britain, 1815-1855: A Study of George Combe and His Circle’ (PhD diss., Wisconsin, The University of Wisconsin, 1969), 16–17, 21–26.

[7] De Giustino, 2.

[8] ‘The Phrenological Society in New York’, Newark Daily Advertiser, 15 March 1837.

[9] For example, see ‘Phrenology’, Glasgow Argus, 1 December 1836, Mitchell Library, Glasgow.

[10] ‘Mr. Combe’s Lectures on Phrenology’, Glasgow Argus, 28 April 1836, Mitchell Library, Glasgow.

[11] ‘On Monday Evening, We Had the Pleasure...’, Commercial Advertiser, 20 September 1837.

[12] Samuel E. Cornish, ‘Phrenology’, The Colored American, 23 September 1837.

[13] ‘Anti Phrenology’, The Colored American, 14 October 1837.

[14] ‘Phrenology Tested (from Zion’s Watchman)’, The Liberator, 22 September 1837.

[15] ‘Sarah M. Grimké to Theodore Dwight Weld [1 February 1838]’, in Letters of Theodore Dwight Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah Grimké, 1822-1844, ed. Gilbert Hobbs Barnes and Dwight Lowell Dumond, vol. 2 (Gloucester: Peter Smith, 1965), 527–30.

[16] Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself (Hartford: Park Publishing, 1882), 299–300.

[17] George Combe, Notes on the United States of North America, During a Phrenological Visit in 1838-39-40, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: MacLachlan, Stewart, & Company, 1841), 190.

[18] James McCune Smith, ‘Mr. George Combe’s Lectures’, The Colored American, 18 May 1839.

[19] Philip A. Bell, ‘Death of Dr. Jas. McCune Smith’, The Elevator, 22 December 1865.