‘Our Faults – Remedies’

James McCune Smith Responds to Critics and Summarizes His Lifelong Contributions to the African American Press

Of my total time over the past week dedicated to working on my biography of James McCune Smith, a pretty large chunk of it has been spent organizing my past research on his writings for the African American press and other publications. As I was trying to locate certain things I remembered him writing in various articles, I found I kept having trouble finding what I was looking for among my research documents and the thousands of images and PDF scans and transcripts of articles that I’ve amassed over the last several years. The way I had initially organized my research had worked pretty well when the volume of materials I was working with was relatively small. But since they’ve ballooned, I found my work – including getting started on new posts for this newsletter – hampered by the lack of a uniform, easy-to-follow system of organization. So, I heaved a big sigh, put my writing notes and outlines and drafts aside, and started putting all my research in order. I’ve happy to say I’ve found what I’m confident is a system that will prove very effective and not take too long to implement.

Also, since I have mostly been working on another full-time project for well over a year, some of my memories of exactly what McCune Smith wrote, and when, and the contexts in which he wrote it, have faded here and there or become a little scrambled. This reorganization, then, is also immensely useful in this regard – it’s refreshing and restoring the biography and collected works of McCune Smith that I’ve been carrying around in my head.

So, I thought I’d share with you another act of recollection and writing things down for future reference – one that I mentioned in my last post for this newsletter. It’s an editorial that McCune Smith wrote in the last year of his life, in which he summarized his history with the African American press. This editorial was such an exciting find – with its guidance, I have been able to find many more works by McCune Smith that hadn’t yet been identified as his, including the letter to the editor of the Glasgow Chronicle I wrote about in my last post. It’s also continuing to guide my search for more.

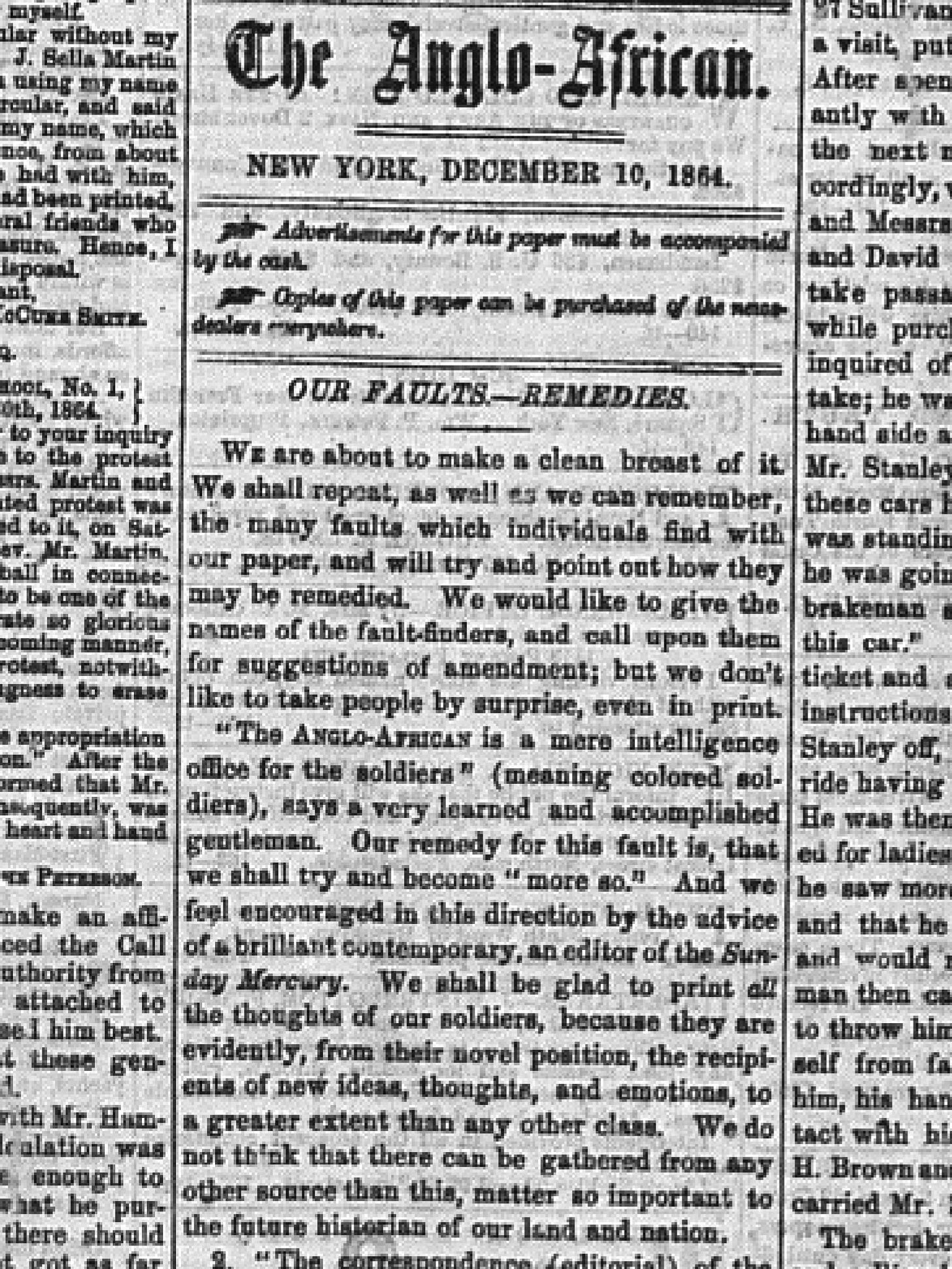

When he wrote ‘Our Faults – Remedies’ for The Anglo-African’s 10 December 1864 issue, McCune Smith was serving one of his many stints as co-editor – or perhaps more precisely, as acting editor – while its head editor and proprietor Robert Hamilton was on an extended trip in the South reporting on the Civil War. The Anglo-African had become one of the preeminent, if not the preeminent, African American periodical(s) since Douglass’ Monthly had ceased publication in 1863. (Frederick Douglass decided to stop publication of this last struggling iteration of his newspaper to devote his time to recruiting African American troops for the Civil War.) As Debra Jackson writes for the New York History journal, ‘The power and influence of the Weekly Anglo-African stemmed from the bold vision of its editors, who provided unflinching, trenchant analysis on all the critical issues of the day.’[1] Robert’s brother, Thomas Hamilton, had founded the original Anglo-African publications in 1859, the literary Anglo-African Magazine and the Weekly Anglo-African newspaper. The Magazine ceased publication in 1860, but the newspaper was published until 1865, with the exception of a few-month’s interruption in 1861. Thomas Hamilton had sold it early that year in order to put it on a better financial footing, but its new editor turned it into a narrowly pro-colonizationalist paper and changed its name. Robert Hamilton revived the Weekly Anglo-African – later simply the Anglo-African – that summer, under its original ethos of presenting all sides of debates over issues of concern to African Americans.[2]

McCune Smith was deeply involved in all the Anglo-African publications from the very beginning, writing essays, articles, and editorials, placing ads, soliciting funds, and serving as assistant editor or acting editor as needed or whenever he could spare the time. But while it was the last African American periodical to publish his work and for which he would serve as an editor, it was far from the first. As McCune Smith writes in ‘Our Faults,’ he was ‘rather an old hand at the bellows editorial’ and indeed, at contributing in various ways to the quality and survival of the African American press.

‘Our Faults,’ as you can see from the reproduction of the editorial in this post, is McCune Smith’s response to a range of readers’ complaints and criticisms. One reader complained that the Anglo-African dedicated too much space to Civil War soldiers’ reports and impressions; McCune Smith replied that not only did the paper not devote too much space to what they had to say – they should give these soldiers even more space in their columns, since their expressions of ‘new ideas, thoughts, and emotions’ were such a rich source of ‘matter so important to the future historian of our land and nation.’ McCune Smith was well placed to recognize this – he himself had long engaged in historical writing and study, including of African American veterans of the Revolutionary War.[3]

Another reader complained that the Anglo-African contained too much frivolous material, such as details of women’s dress and how they entertained visitors. McCune Smith replied, much more sarcastically in this case, that accounts of the ‘excellencies’ of ‘colored ladies’ were ‘as fit subjects for pen-painting’ as those of ‘white ladies’ in other papers. (McCune Smith often used the language of visual art to refer to literary depictions of people and their lives.) Besides, these reports came from the pen of a ‘man, humbly seeking to elevate his people [who] travels all day and far into the night’ who, after undergoing all the hardships associated with travel in a racially hostile environment, who fittingly expressed his gratitude this way for the gracious and generous hospitality he received. Here, McCune Smith made it clear that he was referring to Hamilton’s reporting from the road on how the Civil War was going in the South.

Lastly, McCune Smith responded to complaints about the ‘wishy-washy, uncertain, unsatisfying lucubrations to be found in the editorial columns proper.’ Here, he referred to his own editorials, with self-deprecating humour. He responded that the only way to remedy this problem was for readers who made this complaint to write and send in their own editorials, which he promised to print. As for himself, he was ‘too old to mend’ since he had ‘labored longer at this oar than any live black man.’ Then, McCune Smith went on to include an abbreviated summary of his very long, rich history of contributions to the African American press since its founding era, as well as to other publications. As you can see in the editorial, this list consists of William Lloyd Garrison’s groundbreaking abolitionist paper The Liberator, an unnamed ‘foreign paper’ (referred to in the last post for this newsletter and which I’m still trying to track down), The Colored American (‘Fylbel’ refers to Philip A. Bell, another pioneering African American newspaperman and McCune Smith’s close lifelong friend), the abolitionist and temperance paper Northern Star and Clarksonian (not by name), published by Stephen Myers and edited by James W. C. Pennington, Thomas Hamilton’s first paper the People’s Press, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, and the Anglo-African publications.

While impressively long, this list is not exhaustive; my research and the research of others have revealed that McCune Smith contributed to other periodicals as well, as you’ll likely see in the pages of this newsletter and certainly in the biography. For example, in other writings – most of them predating this one – others or McCune Smith himself identified him as an editor or contributor to other African American publications. [4] But the brief history that McCune Smith provided here has been and continues to be an invaluable guide for uncovering the absolute wealth of previously unknown McCune Smith writings that still do, or hopefully still do, exist.

As you can also see, McCune Smith was looking back here at this part of his life with deep satisfaction. As he wrote, his contributions to the African American press had been and continued to be ‘throughout, a labor of love’ in which he always, despite errors he made from time to time, ‘meant to do well.’ This work had, except for his tenure in 1839 as co-editor of The Colored American, always been done with no financial reward. Like so much of is life’s work, McCune Smith’s labours on behalf of the African American press had always been done for the dual purpose of helping others improve their own lives while satisfying the need for an outlet for his restless and expansive intellect.

Lastly, McCune Smith write this editorial with the expectation that he would not live much longer. McCune Smith had been struggling with bouts of ill health for quite some time at this point, evidently from a chronic cardiopulmonary condition. It was severe enough to intermittently keep him from practicing medicine or even confined him to his home in the last three years or so of his life. But, as it turned out, McCune Smith was not correct when he wrote: ‘A few more scribblings and the old pen will be shelved.’ He would live about eleven more months after writing this editorial, and continued to write for the Anglo-African for much of that time. But, given his abiding religious faith and his confidence that his death would take place while the Civil War changed world history by ending the legal institution of slavery once and for all, McCune Smith was satisfied. He wrote of the impending end of his life with a level of equanimity that we can all only wish for as we face our own.

P.S. In case you’re wondering how I know this anonymous editorial, like the one in the previous issue of this newsletter, was written by McCune Smith - well, again, there are many clues. For one, some of the details of McCune Smith’s history with the African American press contained in this editorial match biographical information that’s well-attested, particularly his long tenure as a correspondent to Frederick Douglass’ Paper. Cross-referencing between this and other editorials in the Anglo-African, including those in which Robert Hamilton identified McCune Smith as a co- or acting editor helps establish that this one is by him. McCune Smith identified himself as the author of most of the leading editorials, such as this one, of the Anglo-African around this period in a letter to his friend Gerrit Smith. And, he signed this one ‘S,’ as he did in some other editorials that can be identified as his through biographical or other details.

[1] Debra Jackson, ‘“A Cultural Stronghold”: The “Anglo-African” Newspaper and the Black Community of New York’, New York History 85, no. 4 (2004): 331–32, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23187347.

[2] Amy M. Cools, ‘The Life and Work of Dr. James McCune Smith (1813-1865)’ (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2021), 162–63, https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/38333; Jackson, ‘A Cultural Stronghold’, 336.

[3] For example, see William C. Nell, The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Persons: To Which Is Added a Brief Survey of the Condition and Prospects of Colored Americans (Boston: Robert F. Wallcut, 1855), 161–62, https://archive.org/details/835279be-31d1-4399-9df3-c9902ba0955a/page/n161/mode/2up?view=theater.

[4] For an account of McCune Smith’s history with the African American press, see Cools, ‘Life and Work’, 148–86, https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/38333. It’s already a little out of date since I and others have uncovered more McCune Smith writings since then.