This post is rather late: I intended to write one before I returned home from New York, but between one thing or another (weariness from long days of intensive archival research, driving from place to place, a crowded airport with no good place to sit and work, and jet lag on the layover for my connecting flight) I didn’t. Peering closely at thousands of documents - often in hard-to-read handwriting and blurry type - punctuated by typing up notes so I could find everything later is quite hard on the eyes, neck, and shoulders. So each time I had every good intention of writing up another post, all I could bring myself to do was to walk or laze a bit in the open air, do a few cardio or stretching exercises to loosen up my tense muscles, or go to bed ridiculously early. Anyway, I’ve rested and gotten caught up on a backlog of work. I’m still in the process of further organizing all that research I did in New York and writing up more reference notes, but that’ll take awhile.

The Gerrit Smith Papers at Syracuse University is a collection I’ve been anxious to delve into deeper for some time. When I was a doctoral student at the University of Edinburgh, I had my research trip to New York state all planned out and paid for, and Syracuse was on my itinerary. But that was when the Covid pandemic restrictions were put in place, the archives shut down and my flights were cancelled. Though I’d made it to New York City archives in the interim, I never did make it to Syracuse before this trip, mostly due to budget restraints - for one thing, it’s not as readily or affordably accessible from Scotland or northern England as New York City is! I also had lots of generous help from others who had images of all the James McCune Smith correspondence in the Gerrit Smith Papers, and other documents besides, which they kindly shared with me, and part of the collection is also digitized and available online. So, since I had already had access to the bulk of the most crucial sources pertaining to McCune Smith, I put off my trip to Syracuse until I had the funding and time to get there. I just knew, however, that there would be lots of hard-to-find sources if I dug deeply into that massive collection myself, and this turned out to be true. After all, pretty much everyone in the world of political, social, and religious reform corresponded and worked with Gerrit Smith, so there were bound to be hidden gems to be uncovered by digging deeply into this largest collection of his papers anywhere. I’m so grateful that I had the British Academy research funding to help me finally take that trip!

There were countless letters and other artefacts that provided fascinating insights into and details of events and topics relevant to McCune Smith and his world, too many to discuss in this post. But I will discuss two particularly exciting things I found: letters co-authored by McCune Smith. I’ve never seen these letters before nor have I seen them cited or discussed anywhere. That's likely because they’re both located in unexpected places.

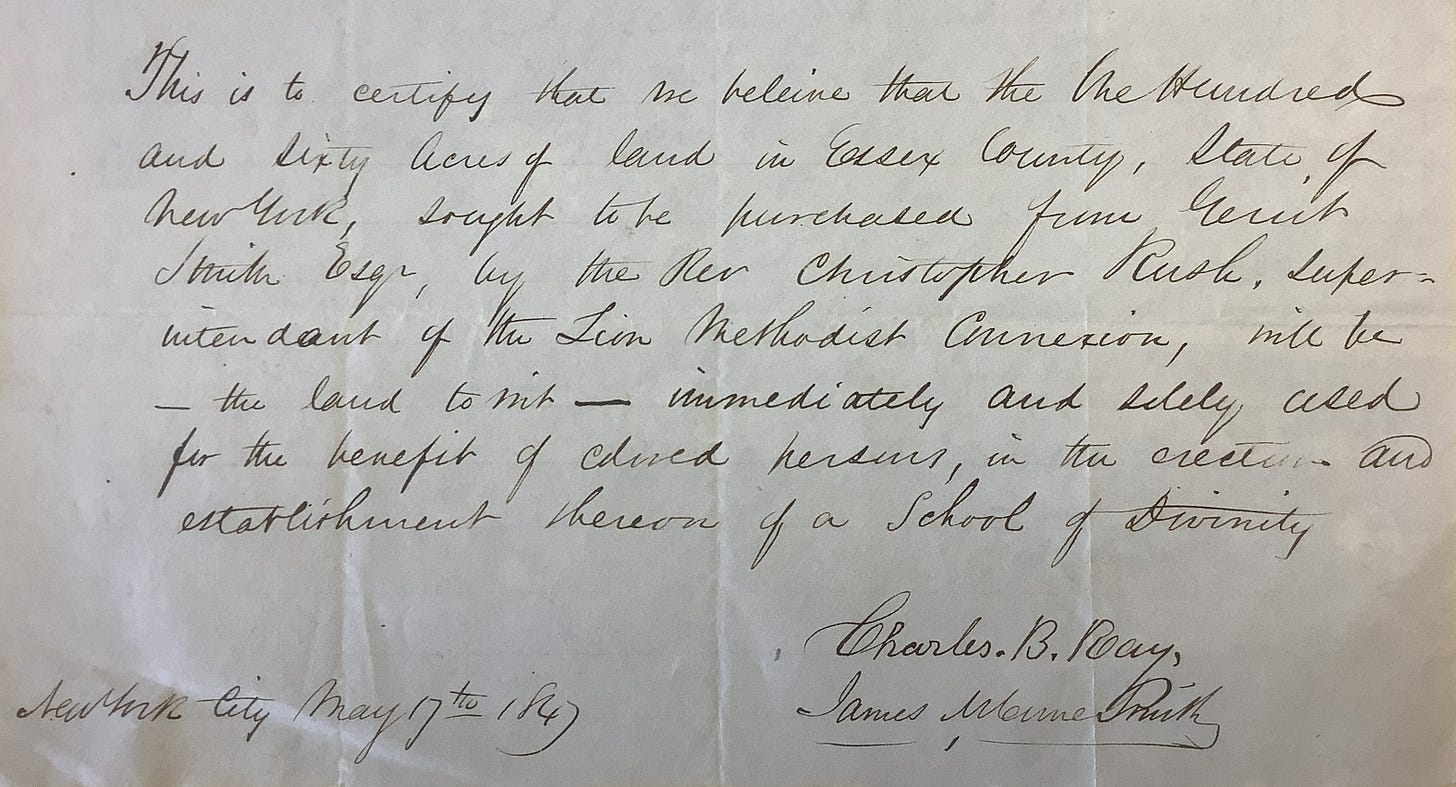

The first is a short letter - perhaps better described as a note - found within a folder of Smith’s bills and receipts. I was looking there because McCune Smith had many financial dealings with Smith. As my research for my doctoral thesis and then biography of McCune Smith has yet again shown, an absolute wealth of information can be gleaned from financial and legal documents about a person’s life, family, friendships, connections, community, work, and more. I was hoping to find bills and/or receipts written by either Smith, McCune Smith, or both, or cashed checks, or inventories, or similar artefacts. I didn’t, however, expect to find a short letter. In fact, it’s the only such thing I found in any of the bills and receipts folders I looked at.

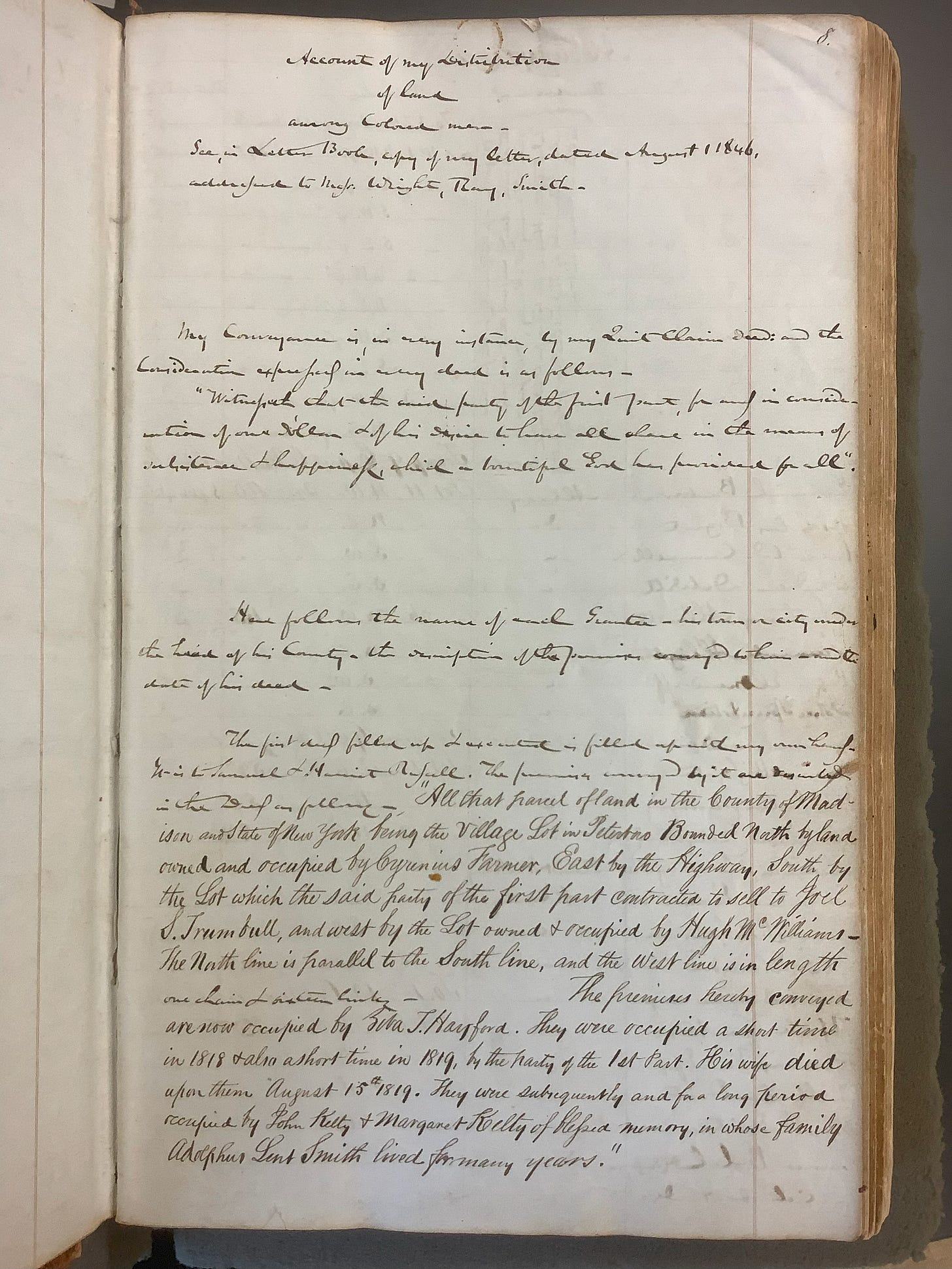

The short letter is in McCune Smith’s handwriting (thankfully tidy - unlike Smith’s, which is often nearly impossible to decipher; see page of Smith’s Land Book above), and signed by him and Charles B. Ray. Ray helped McCune Smith administer Smith’s land grant scheme, as I described in a previous post. In this brief letter, McCune Smith and Ray attest that they believed that Christopher Rush intended to use the 160 acres he wanted to buy from Smith ‘immediately and solely used for the benefit of colored persons, in the erection and establishment of a School of Divinity.’ Rush, a founding member of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in New York City and superintendent of the Zion conference (or ‘connexion’) of African Methodist Episcopal churches. Evidently, Smith was very concerned that all properties connected with his land grant scheme would contribute to the cause of helping black New Yorkers achieve self-sufficiency and financial security, including lands he sold at very low prices to some who were not poor but who nonetheless could help support the project. And, as both Smith and Rush knew very well, one of the many impediments to African Americans’ flourishing in New York was the barriers they faced when trying to enter theological seminaries. McCune Smith’s friends Isaiah DeGrasse and Alexander Crummell, for example, had been denied the opportunities to study at New York City’s General Theological Seminary on an equal footing and to formally graduate on account of race.

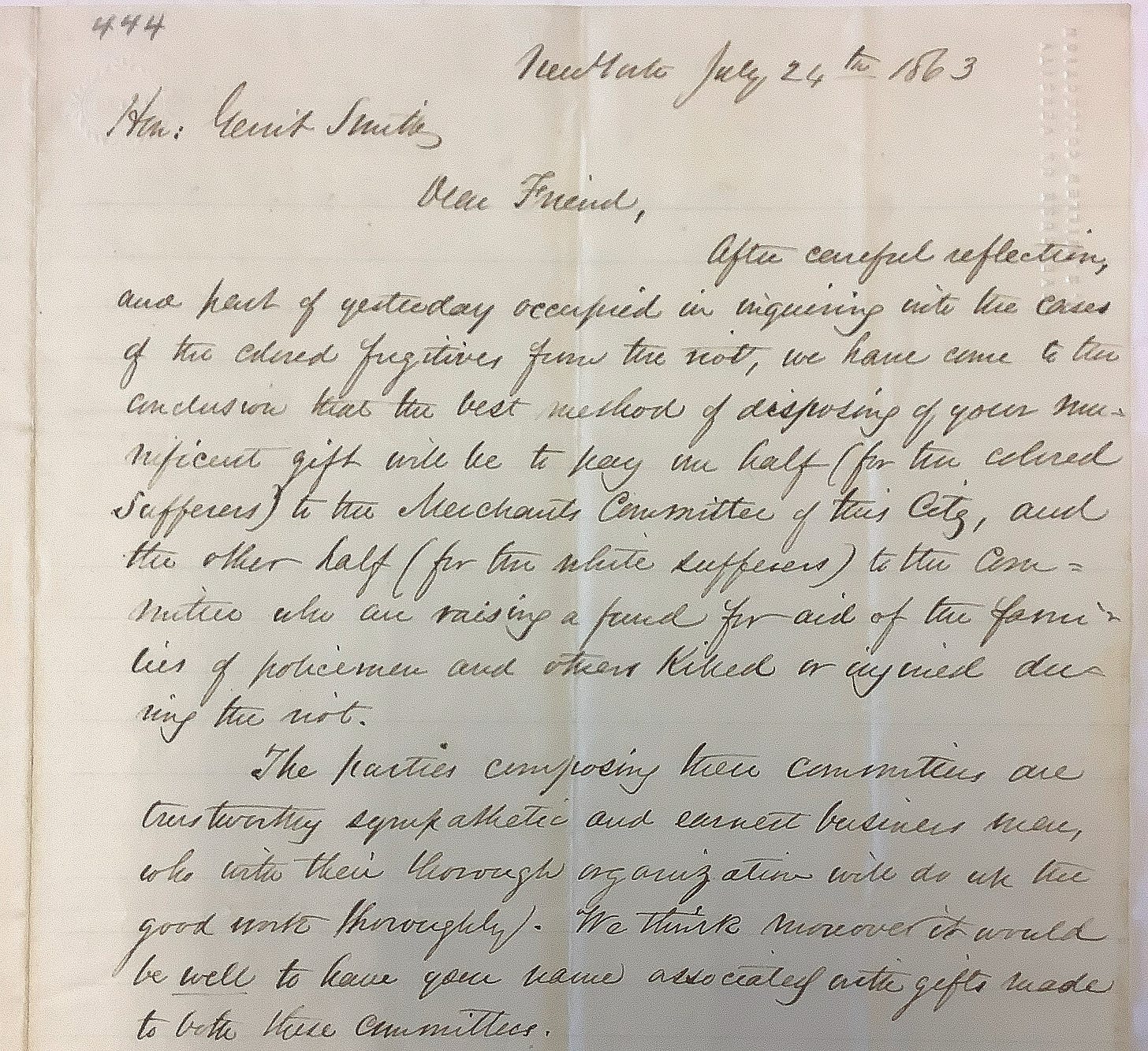

The second letter was even more exciting. That’s because it’s from a time period in McCune Smith’s life for which sources are particularly hard to find - the last two-plus years. That’s largely because McCune Smith was frequently ill, often so seriously that he was housebound, due to the chronic cardiopulmonary disease that would eventually take his life. As I wrote in a previous post, one of these bouts of severe illness meant that he wasn’t at the Colored Orphan Asylum when it was attacked and burned down during the horrific Draft Riots in New York City of 13–16 July 1863. What I didn’t know, and what I learned from this and another letter written by McCune Smith’s friend Simeon S. Jocelyn to Smith two days earlier, is that Gerrit Smith asked McCune Smith and Jocelyn to administer his $1,000 donation to help relieve victims of the rioters, both black and white. In this co-authored letter (also mostly in McCune Smith’s hand), McCune Smith and Jocelyn recommend that the money be conveyed to two committees already in existence. One was the Merchants Committee founded by businessmen of the city who were shocked at the murder, assaults, and robberies inflicted on black New Yorkers, and organized a huge relief effort. The other was, as McCune Smith wrote, ‘a committee who are raising a fund for aid of the families of policemen and others killed or injured during the riot.’ As McCune Smith and Jocelyn would have well known, though a huge contingent of the rioters were angry Irish New Yorkers who considered black New Yorkers to be their economic and social competitors and even enemies, the children of the Asylum and other black New Yorkers were also protected, sheltered, and otherwise aided by Irish police officers and other sympathetic Irish and German New Yorkers, often at great danger to themselves.

This letter was in Jocelyn’s folder among Smith’s incoming correspondence because that’s how Smith himself filed it. McCune Smith wrote or co-signed many letters, and I hoped to find more of them looking in the folders of his friends and connections. One of the first I looked in for letters that might pertain to McCune Smith’s later life was Jocelyn’s because, as I discovered when doing research for McCune Smith’s biography, he and his family moved next door to Jocelyn’s home in Williamsburg. That was well after McCune Smith and Jocelyn authored this letter - McCune Smith and Malvina purchased the Williamsburg house on 8 March 1865, according to the deed - but it’s one of several bits of evidence that indicate that they enjoyed a long and evidently increasingly close friendship. This 1863 letter, and the one Jocelyn wrote to Smith two days before, also reveal that McCune Smith had gone to Williamsburg for a few days after the riots, perhaps as a precaution in case of further violence, or perhaps because other friends had fled there, or perhaps because he and Malvina were thinking of leaving New York City themselves. In any case, as the letter from McCune Smith and Jocelyn reveal, McCune Smith had recovered well enough that he said he had the time and energy to help administer Smith’s donation. These newly learned details, of course, will be added to and fleshed out in the biography as I continue to go through the editing process with my publishers.

Hope you found this of interest, and I look forward to sharing more fascinating stories of McCune Smith and his world with you!