Last week, I finally made it into the Family History Centre at the offices of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Edinburgh. I had been scheduled for a research visit when the Covid pandemic first hit, but the Centre closed down and stayed closed for quite a while. Since then, one thing or another intervened and I never made it in. One of the very first things I did, then, when resuming research for the biography was to book a new research appointment there.

As those who have ever researched your family history online likely know, the LDS Church’s FamilySearch website hosts a fantastic array of scanned sources such as land records, birth, death, and marriage registers, wills and probate documents, military records, and so on. It was one of the most important sites for me when I researched James McCune and Malvina Barnett Smith’s family history for my PhD thesis and the three-part journal article I wrote for the Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society’s 2020 issue.[1] You may also know that images from some sources are not available online; they’re only accessible from one of the Family Research Centres. Those records were the ones I went to track down.

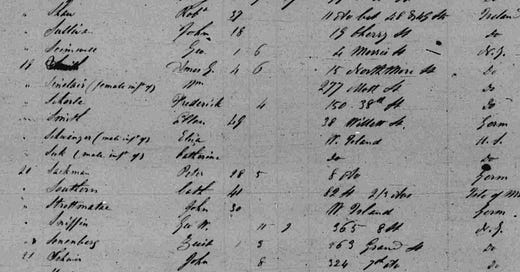

I found many valuable sources, but the ones that really got to me were three entries in the scanned pages of a Manhattan register of deaths from 1854. The first one I found, when conducting searches under the names of the Smith family children, was indexed (as in, the information on the pages had been transcribed and made searchable) as ‘Amos G. Smith.’ Since the year, the middle initial, the last name, the places of birth and death, and the year were all matches, I was immediately nearly certain that I had found what I was looking for, though the first name was wrong. After all, transcription errors are quite common when people are indexing handwritten records, and no wonder – sometimes the handwriting is sloppy or the way the writer formed their letters was unusual; sometimes the ink did not soak into the paper evenly so parts of the words or letters fade away; sometimes the uneven surface of the paper or the surface below the paper caused the writing implement to jump a bit, so that the ink didn’t make it onto the paper in places.

The latter appears to have happened in this case. Sure enough, when I looked at the entry in the image of the page rather than the transcribed information for this child, I found that lots of other things matched as well. The given address was 15 North Moore Street, the Smith family’s address from May 1847 to sometime in 1864 or maybe early ’65 (still trying to nail down just when they moved). The date of death in the register, 19 September 1854, matched a newspaper announcement of the tragedies the Smith family suffered that summer. And the burial place is correct – this child was buried at Cypress Hills in Brooklyn, like most of the Smith family, many members of their extended families, and many friends as well.[2]

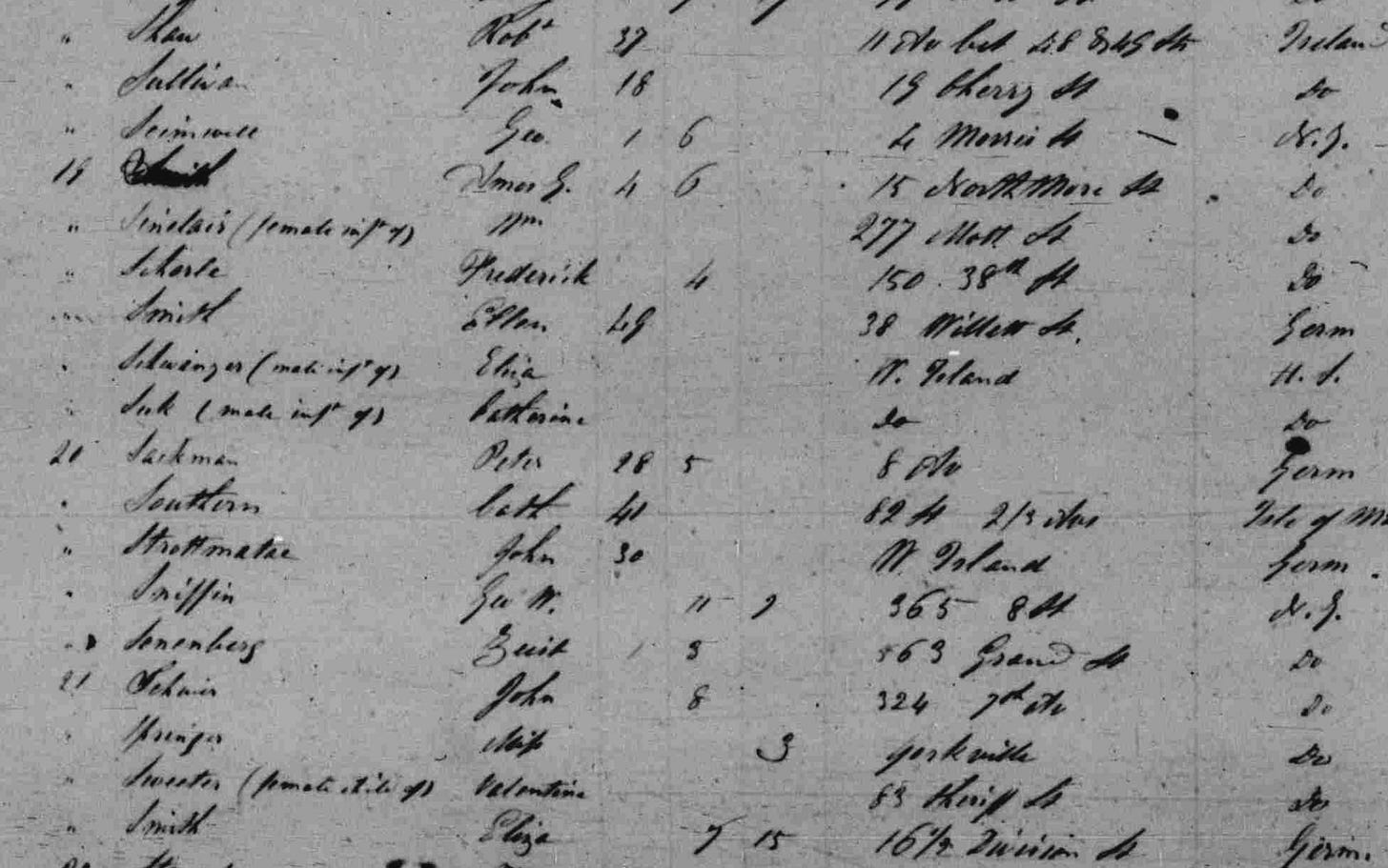

So, who is this child, and what’s their name? Well, that’s a good question. The entry indexed as ‘Amos G. Smith’ could easily be read ‘Smith, Amy G.’ if you consider that the bottom half of the curve of the ‘y’, as well as its tail, might be missing. If you read it this way, it matches an entry in a public document in which the handwriting is perfectly clear: the 1850 US Census entry for the household of Lavinia Smith (McCune Smith’s mother). It includes a listing for ‘Amy G,’ 6 months old, right at the end. So far, it looks like we have perfect match and that we don’t need confirm the name any further. But… In the following month, Frederick Douglass’ Paper published a notice of deaths that had occurred mostly within the previous month. Compiled by Martin Robison Delany, the famed abolitionist and regular contributor to Frederick Douglass’ Paper, the notice opens: ‘DIED. In New York, August 13, FREDERICK DOUGLASS, aged four months and 27 days; August 27, PETER WILLIAMS, aged two years and five months; Sept. 19, ANNA GERTRUDE, aged 4 years, six months and twelve days children of Melvina and Dr. James McCune Smith.’[3] Until I found the entries in the Manhattan death register, Delany’s notice was one of my main sources for the lives and deaths of these three children. But why is the Smith child who died on 19 September identified in it as Anna?

Well, the most obvious explanation is a simple error; perhaps ‘Amy’ was again written in unclear handwriting, looking this time like ‘Anna.’ But perhaps there’s another explanation. You see, McCune Smith and Malvina had already lost a child some years back who was also named Amy. McCune Smith told the sorrowful story of her life and death in a heartbreaking letter to his friend Gerrit Smith, who had likewise suffered the loss of his own child. On 6 February 1850, he wrote,

Dear friend, Your letter finds me stricken with grief for the loss of my first born, my dear little Amy. After a year of ailment, at times painful and distressing, always obscure, and which she bore with child-like patience, it pleased God to take her home to the company of Cherubs who continually do Praise Him. You have been afflicted in like manner and know the bitterness of it: for one thing, I feel deeply grateful, her mind was serene to the last, and intelligently hopeful of a Blessed Immortality. She died on Christmas eve and lacked 5 days of six years of age. My dear wife was sadly afflicted, and until within a few days I have dreaded a permanent despondency; she is growing more cheerful however, and we both live, in the hope of meeting our dear little one where there will be no more sickness, nor pain nor parting forevermore.[4]

Of all the children he and Malvina lost, McCune Smith would in future refer to their first child, their dearly loved Amy, the most. We can also see that he and Malvina sought to memorialise her in the name of another daughter. But it may also be that the family simply found it too painful to call another child by the name of that lost one, so they came to call her Anna.

The Smith family lost at least one child after that first Amy – perhaps two – and before the three whose names I found in that Manhattan register. One appears only as a name, ‘Mary S. Smith,’ in a burial record for the Smith family plot, with no date.[5] McCune Smith and Malvina did have a daughter named Mary Maude Smith, but since she long outlived her parents, it’s unlikely that her name would appear, as this one does, among the names of the children they lost early. A family bible may also refer to her indirectly, since it says that the Smith’s last child was their eleventh.[6] Only 10 are recorded or even alluded to elsewhere, so if this other Mary existed, perhaps she died in early infancy.

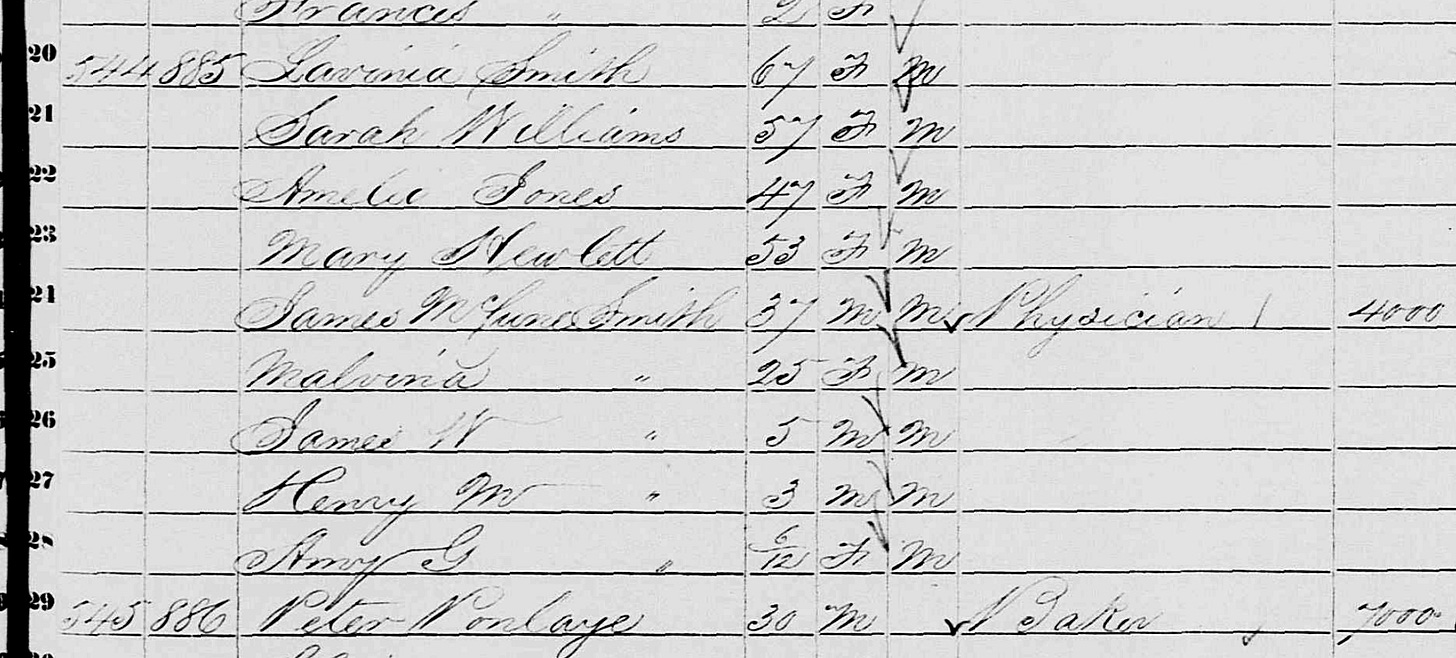

The other child they lost before that terrible summer of 1854 was Henry. His name is recorded in the 1850 census as Henry M. Smith, aged three. He died in the late spring or early summer of 1853. Later that year, in an essay McCune Smith wrote as the New York correspondent for Frederick Douglass’ Paper – explaining the delay between is contributions as he did so – he wrote of this loss in terms just as heartbreaking as he had of the loss of his first child in his letter to Gerrit Smith:

These little sketches were sadly interrupted by the long and painful illness of one whose little chair is vacant by my hearthstone, whose little grave is filled on the hillside; and again and again, as I sit by my easel, brush in hand, spirit fingers weave his golden hair upon the canvas, and those sad eyes light upon me, and spirit voices break the stillness of the night, in cadences now light and airy, now sobbing in keen agony.[7]

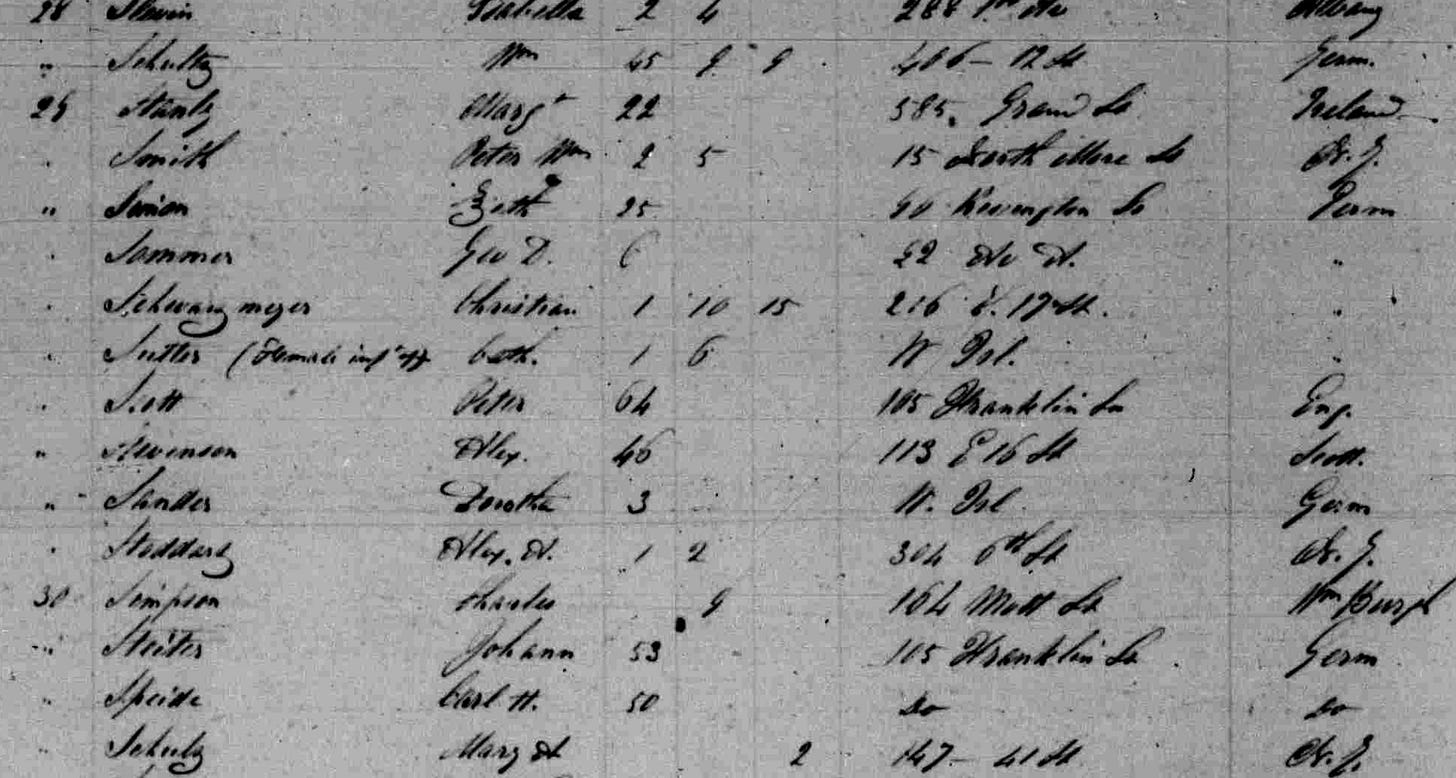

Returning now to the Family History Centre… here I was, with Amy G. Smith’s entry in that Manhattan death register on the screen and the stories of all the Smith family’s lost children in my mind. I look next for entries for the first Amy and for Henry but find that the only such register that had been digitized was one for 1854. So, I look for entries for the other two Smith children who died that year, and sure enough, I find them. Their names were not indexed, so it took some careful scrolling through often very unclear handwriting, as you can see in the photos. But with the information from Delany’s notice in hand, it’s not hard to know where to look. First, I find the listing for the first Smith child who died that terrible summer.

His name was Frederick Douglass Smith. He had a very short life indeed. According to the death register, he died on 13 August, aged 4 months and 28 days, of whooping cough.[8] Now this was curious. According to Delany’s notice, the Smith children were among the “beloved and esteemed citizens, all of whom were dear acquaintances of the humble writer, [who] were swept away from the shores of time and place by that dread pestilence, the Cholera.” The cholera epidemic that was sweeping through New York City in the summer of 1854 was the second of two that had hit the city in rapid succession, the previous one in 1852.[9] This seems to indicate that Delany just assumed the cause of the Smith children’s deaths. I glance back at Amy G.’s entry and find that her cause of death was recorded not as cholera, but as scarlet fever.

The last of the children’s names I sought and found in this register was Peter Williams Smith. According to the Manhattan death register, he died on 29 August, aged 2 years and 5 months. In this case, Delany was right: the cause of Peter’s death was listed as cholera.[10]

As I had done when writing my articles on the Smith-Barnett family and my thesis on the life of McCune Smith, I imagined how awful it would be for James McCune and Malvina Barnett Smith to lose so many children, at least five in all, and three of them within the span of two months. McCune Smith never wrote specifically about little Amy G., or Frederick, or Peter, at least nothing that anyone has found yet, to my knowledge. He did, however, write again of his deep sorrow for their deaths in an essay for Frederick Douglass’ Paper – his regular contributions again interrupted by the loss of children – but kept his remarks short:

The leaves are falling in our lane; and the trees, stripped and gaunt, seem prepared to wrestle with the coming storms; and the blossoms are withered, and the little feet no longer patter in our door-way, and

“Oh, I am aweary, aweary!”[11]

And I couldn’t help but think that, as a physician, McCune Smith must have felt that much more pain, perhaps always wondering how his skills as a healer could fail to save so many of his children.

A year and two days after little Amy G.’s death, the Smith family welcomed a new baby girl, Mary Maude. With her birth, the Smith family once again had more than one child around, and their eldest son James Ward again had a little sister.[12] Mary Maude was followed by three more children, Donald Barnett, James Murray, and Guy Beaumont. James McCune and Malvina Barnett Smith would never again suffer the pain of losing children – all the rest long outlived their parents.[13]

[1] Amy M. Cools, ‘Roots: Tracing the Family History of James McCune and Malvina Barnett Smith, 1783-1937, Part 1’, Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society 37 (2020): 43–52; Amy M. Cools, ‘Roots: Tracing the Family History of James McCune and Malvina Barnett Smith, 1783-1937, Part 2’, Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society 37 (2020): 53–62; Amy M. Cools, ‘Roots: Tracing the Family History of James McCune and Malvina Barnett Smith, 1783-1937, Part 3’, Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society 37 (2020): 63–79; Amy M. Cools, ‘The Life and Work of Dr. James McCune Smith (1813-1865)’ (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2021), https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/38333.

[2] “New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1795-1949”, digital image s.v. “Manhattan Register of Deaths: Amy G. Smith, 1854,” FamilySearch.org.

[3] Martin R. Delany, ‘Died’, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, 6 October 1854.

[4] ‘James McCune Smith to Gerrit Smith, 6 February 1850’, Gerrit Smith Papers, Syracuse University Libraries.

[5] ‘Interment Record for Smith Family Plot at Cypress Hills Cemetery’.

[6] Family Bible of Antoinette Martignoni, Great-Granddaughter of James McCune Smith.

[7] James McCune Smith, ‘Heads of the Colored People - No. VII: The Inventor’, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, 9 September 1853. In the first essay in this series of life sketches of poor and working-class African American New Yorkers, McCune Smith described them as “word paintings” and his pen as the brush that created them. He described the loss of that first Amy again in that essay, this time in much the same style as he did Henry’s loss. See James McCune Smith, ‘“Heads of the Colored People,” Done with a Whitewash Brush: The Black News-Vender’, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, 25 March 1852. Unlike in his letter to his friend Gerrit Smith, McCune Smith did not refer to his lost children by name in either of his essays; in fact, whenever he referred to his family members in pieces he wrote for publication, he kept their names private.

[8] “New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1795-1949”, digital image s.v. “Manhattan Register of Deaths: Frederick D. Smith, 1854”, FamilySearch.org.

[9] Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City To 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 589, 595.

[10] “New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1795-1949”, digital image s.v. “Manhattan Register of Deaths: Peter Wm Smith, 1854,” FamilySearch.org.

[11] James McCune Smith, ‘Heads of the Colored People - No. X: The Schoolmaster’, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, 3 November 1854.

[12] ‘James McCune Smith to Gerrit Smith, 6 October 1855’, Gerrit Smith Papers, Syracuse University Libraries; 1860 United States Census, New York, New York County, New York, digital image s.v. “Jas. M. Smith,” FamilySearch.org.

[13] Cools, ‘Life and Work’, 30–33.