My biography of James McCune Smith will begin where his life story began, and where most of his life story took place: in New York City. But perhaps fittingly for this transatlantic newsletter, this first installment will tell a Glasgow story. It also just so happens that this piece is written by an American who lives in Scotland, about a piece written by an American living in Scotland. It was also in Scotland that I first came across McCune Smith, and I found him the most fascinating historical person I had come across in a very, very long time. My fascination has in no way abated. I hope you’ll feel the same way.

As you will know from the introductory piece for this newsletter, McCune Smith earned three degrees from the University of Glasgow: Bachelor of Arts (1835), Master of Arts (1836), and Doctor of Medicine (1837).[1] What you may not know is that McCune Smith went abroad to pursue a higher education because his applications to American colleges were rejected on account of race. It may seem extraordinary that McCune Smith went all the way to Europe to receive a college education. But he was ambitious – and his mentor, the Rev. Peter Williams, Jr., was ambitious for him. (Williams was a massively important person in McCune Smith’s life; we’ll certainly encounter him many times in this newsletter.) It was Williams who helped McCune Smith apply to colleges in the United States, and Williams who helped get him into the University of Glasgow.[2] Williams was in contact with abolitionists on the other side of the Atlantic, so it was likely on the advice of his British friends that his protégé McCune Smith applied – or Williams applied on his behalf – to the University of Glasgow as well. After all, Glasgow had a thriving abolitionist movement,[3] and a very large majority of the University’s students had signed a petition to Parliament for the immediate and total abolition of slavery in British colonies.[4]

As I have written elsewhere, McCune Smith was amazed and delighted at the lack of racial prejudice he experienced in Britain and commented on it frequently in his writings. After he arrived at the Broomielaw quay in Glasgow on 16 September 1832, he quickly connected with the city’s abolitionist community. Near the end of the following year, McCune Smith became a founding member of a new abolitionist society, the Glasgow Emancipation Society. It supplanted the Glasgow Anti-Slavery Society, with an expanded mission: rather than focusing its attention on putting a final end to slavery in the British colonies (Parliament had approved a plan to gradually end slavery that summer, with compensation to slaveholders[5]), it was committed to ending every form of slavery wherever it existed.[6]

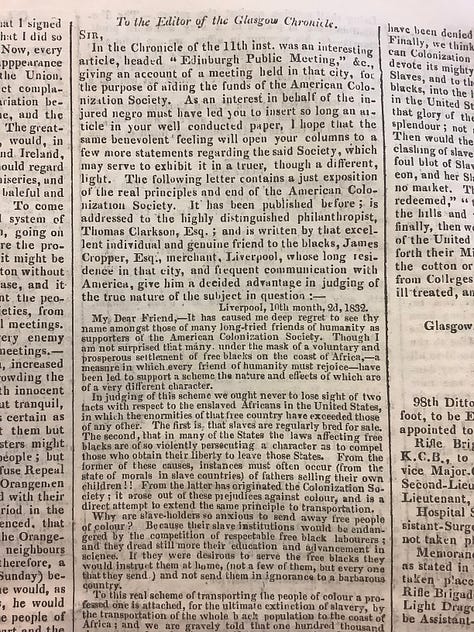

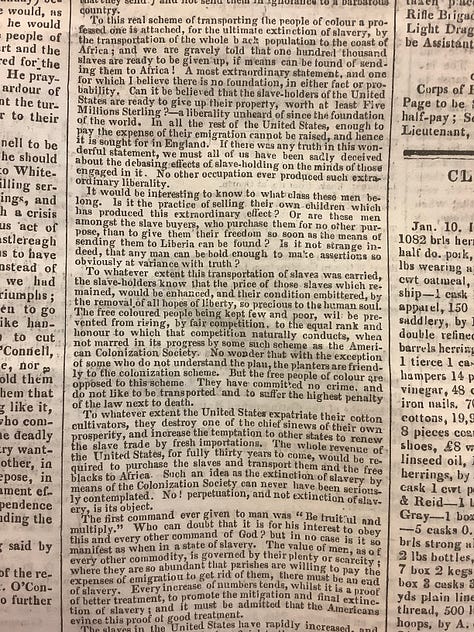

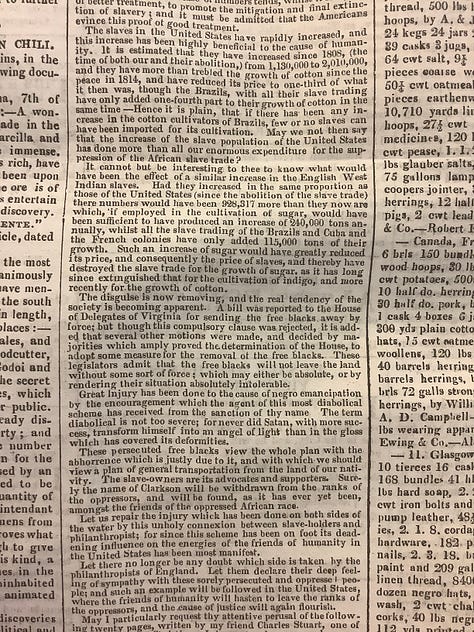

In the meantime, McCune Smith had added his voice to the public debate over slavery and how it should be ended. When McCune Smith arrived in Britain in late summer 1832, Elliott Cresson had already begun making the rounds there, giving speeches and raising money on behalf of the American Colonization Society (ACS). The ACS’s mission was to fund and facilitate the expatriation of free African Americans to colonies in Africa, ostensibly for the benign purpose of giving them the opportunity to live and thrive free from oppression and racial prejudice. But McCune Smith, like so many others, didn’t buy it. Like his mentor Williams, most African Americans, and his new British abolitionist friends, McCune Smith ardently opposed the ACS and all it stood for. They believed the ACS was actually motivated by racial prejudice, and that the effect of their mission was to bolster negative racial stereotypes, weaken African American communities, and strengthen the institution of slavery.[7]

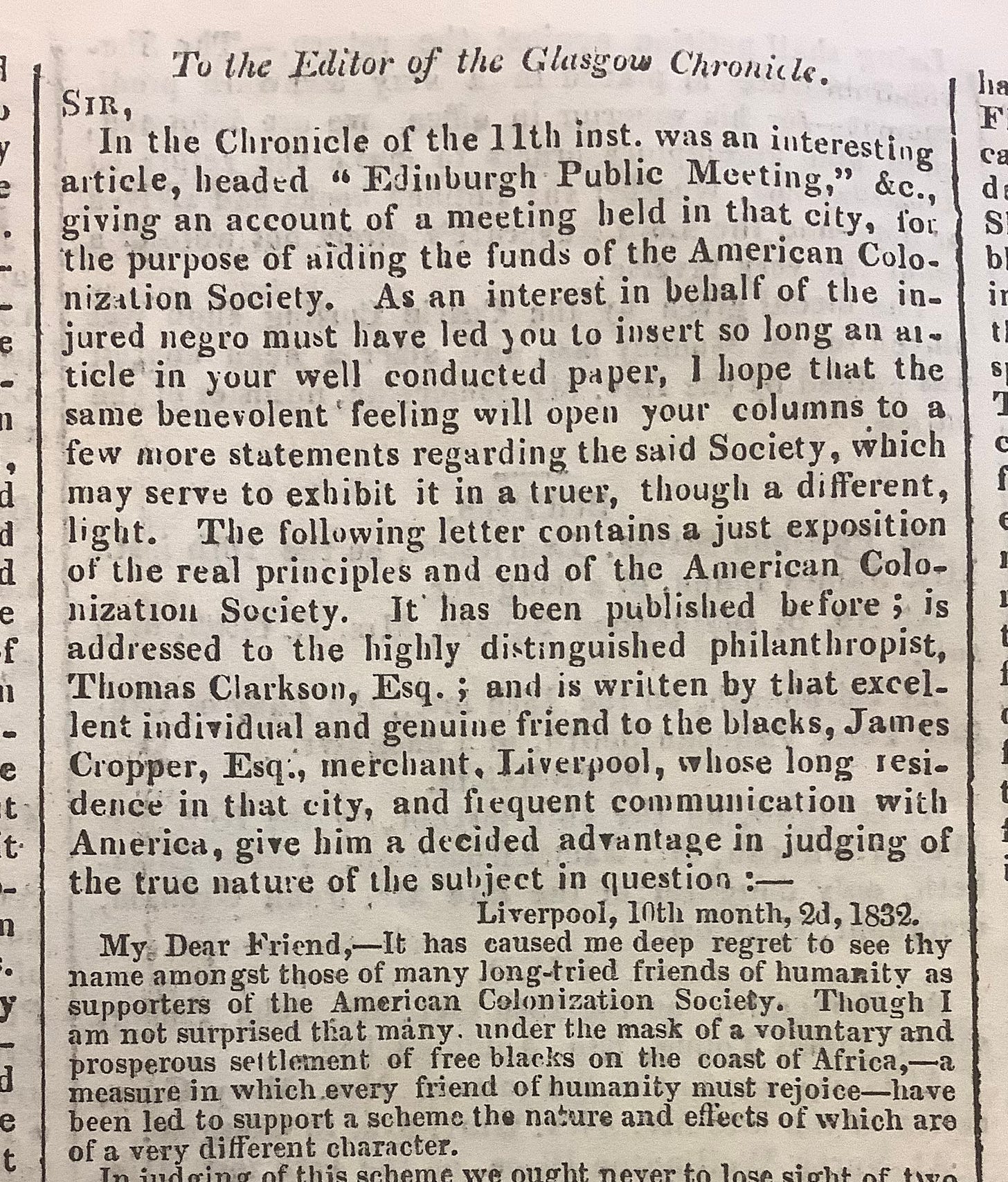

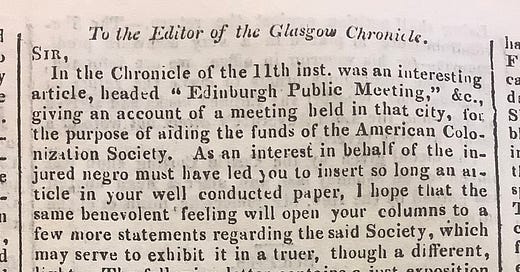

So, it came as no surprise that the first piece by McCune Smith published in a British newspaper that I could find was a letter to the editor of the Glasgow Chronicle of 18 January 1833, vehemently opposing Cresson and the ACS.[8] I found this piece last summer once the archives had reopened following the widespread closures and restricted access during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. While conducting research for my PhD thesis “The Life and Work of James McCune Smith (1813-1865),” I had found an editorial that McCune Smith had written late in his life, which included a summary of his history of involvement with the African American press since its founding era.[9] (We’ll consider that fascinating editorial in a future newsletter.) In that editorial, McCune Smith wrote that “from 1832 to ’37,” he was “a constant correspondent” to a “foreign paper,” which he did not name. I immediately started hunting for McCune Smith works in European (especially British) newspapers, but pandemic lockdowns and restrictions intervened, making it impossible or nearly impossible to conduct searches in newspapers from that period that have not been digitized – which is most of them. As soon as possible after the restrictions eased up, I resumed the hunt. Since McCune Smith was living in Glasgow from 1832-1837 and was deeply involved in that city’s abolitionist movement, I started my search in Glasgow newspapers, especially those with anti-slavery sympathies. Sure enough, I found a letter to the editor in one such newspaper, the Glasgow Chronicle, that fit the bill.

(UPDATE: at the request of a reader, I have updated this post to include photos of the entire letter. You’ll find them at the bottom of this post.)

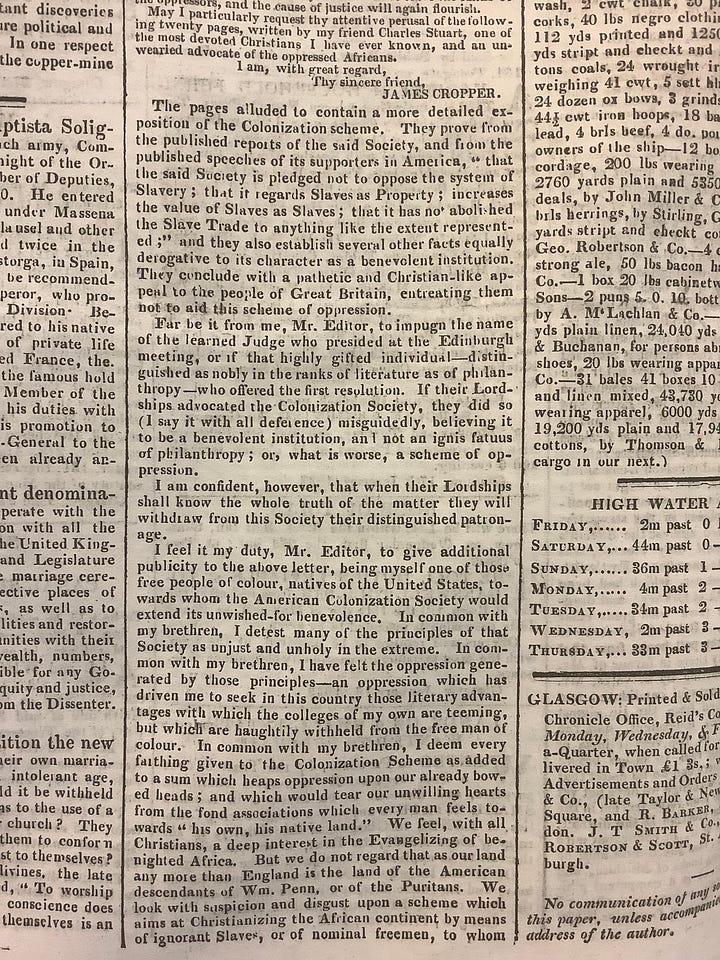

Signed “A Young American” and dated 15 January 1833, McCune Smith’s anonymous letter to the editor introduced a heretofore unheard voice to the debate that Cresson had ignited in Britain – that of a free African American living there who also belonged to the category of people that the ACS had ostensibly been formed to help. After a brief introduction, McCune Smith included the full text of a long letter from one famous British abolitionist, James Cropper (a merchant from Liverpool), to another, Thomas Clarkson. That letter, McCune Smith wrote, ‘contains a just exposition of the real principles and end of the American Colonization Society.’ The ACS’ true mission was, according to Cropper, to help American slaveholders by 1) increasing the monetary value of those they enslaved by reducing the competition of free labour, and 2) decreasing the number of free African Americans in the United States, whose existence there threatened the institution of slavery by showing that African Americans could indeed live freely and thrive outside of that institution.

McCune Smith then buttressed Cropper’s arguments with his own. For one, he wrote, African Americans did not consider Cresson’s and the ACS’ mission to be a benevolent one – far from it. He and his fellow African Americans stood in opposition to all that Cresson stood for, for many reasons:

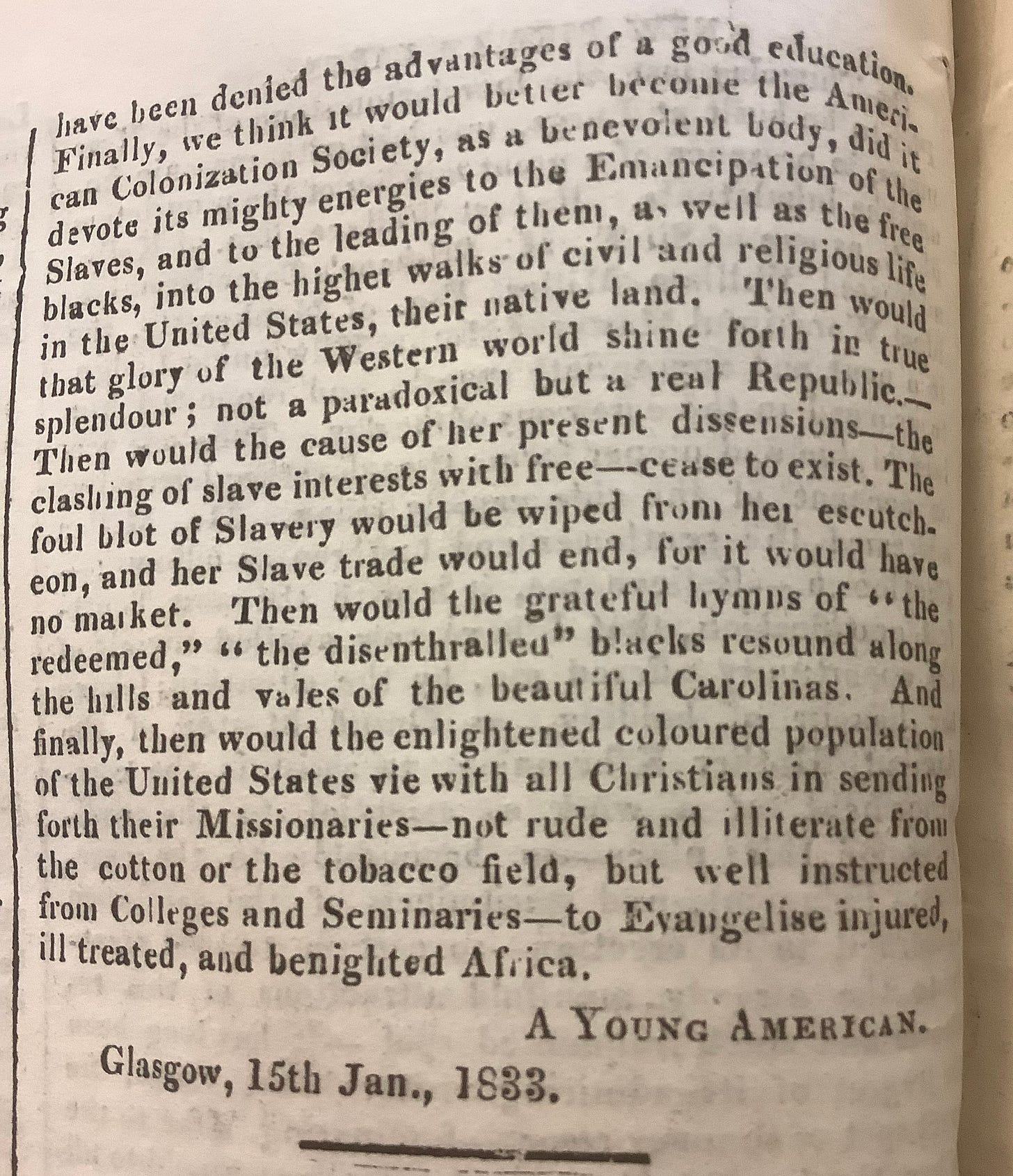

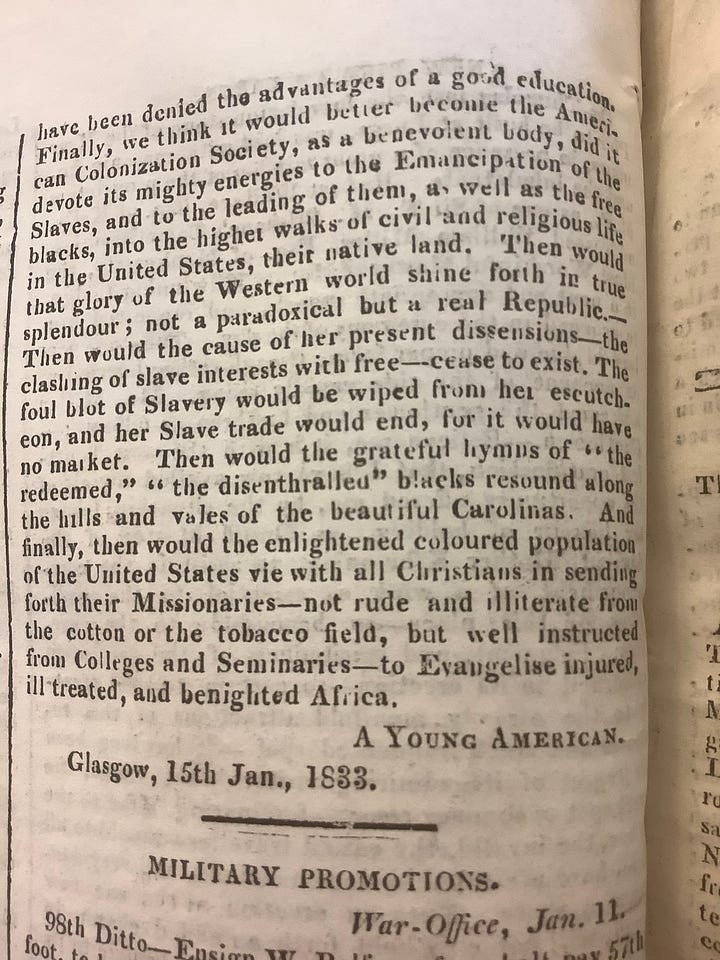

In common with my brethren, I detest many of the principles of that Society as unjust and unholy in the extreme. In common with my brethren, I have felt the oppression generated by those principles – an oppression which has driven me to seek in this country those literary advantages with which the colleges of my own are teeming, but which are haughtily withheld from the free man of colour. In common with my brethren, I deem every farthing given to the Colonization Scheme as added to a sum which heaps oppression upon our already bowed heads; and which would tear our unwilling hearts from the fond associations which every man feels towards “his own, his native land.” We feel, with all Christians, a deep interest in the Evangelizing of benighted Africa. But we do not regard that as our land any more than England is the land of the American descendants of Wm. Penn, or that of the Puritans. …Finally, we think it would better become the American Colonization Society, as a benevolent body, did it devote its mighty energies to the Emancipation of the Slaves, and to the leading of them, as well as the free blacks, into the highest walks of civil and religious life in the United States, their native land. Then would that glory of the Western world shine forth in true splendour: not a paradoxical but a real Republic.’

Given that the ACS’s mission could only hurt, not help, the cause of African American liberation within and without the institution of slavery, McCune Smith hoped that supporters of the ACS who read this letter withdraw their support, now that they knew what really motivated that society and the harm that they caused.

Finding this lost letter to the editor was exciting for so many reasons. It was not so much his expression of opposition to the ACS, since McCune Smith had made that clear in the travel journal he wrote en route to Britain, later published in the pioneering African American newspaper The Colored American, and in many of his best-known writings.[10] This is also true of the devout Christianity he expressed in this letter, and associated hopes that it would spread more widely in Africa, and that among the chief evils of slavery and racial prejudice is that they deny African Americans “the advantages of a good education.” All of these are immensely important – but to those familiar with McCune Smith, quite well known.

Chief among the reasons why I was thrilled by finding this letter is that it shows how early McCune Smith had begun to form and express some of the most important and central themes in his lifetime of authorship. For one, as the letter makes clear, McCune Smith was a patriot who firmly believed that the destiny of African Americans was to save the United States from self-destruction caused by allowing the morally corrosive, socially divisive, manifestly oppressive institution of slavery to continue. McCune Smith argued that all great republics of the past had destroyed themselves by failing to rid themselves of that evil. But the United States had a different fate. African Americans, McCune Smith argued, would lead the way in ending slavery through moral and intellectual means. (McCune Smith only later came to believe that force would also be needed to end slavery, and that African Americans had an essential role to play in that regard as well.) Once slavery was ended, the United States would be transformed from a false to a true Republic, one which was dedicated to protecting the rights and liberty of all her people. McCune Smith elucidated this theory masterfully in an 1841 lecture, published in 1843 as “The Destiny of the People of Color.” I consider it one of his most important and beautifully written works, and it’s thrilling to see him already expressing its central theme when he was still only a nineteen-year-old college freshman. (I’ve written about the intellectual and artistic aspects of “Destiny” here.)

This letter is also particularly exciting because, in it, McCune Smith also introduced another key theme that he addressed at even greater length throughout his writings. When he wrote – employing a Byron quote – that the United States was African Americans’ “own… native land,” and that Africa was no more African Americans’ native land than England was the native land of her American-born descendants, McCune Smith expressed ideas at the heart of another one of his most important theories: that African Americans had come to be a new, indigenous, distinctly American ethnicity. He did not believe that there was a pan-African nationality or a singular black race. McCune Smith believed, rather, that Africa was a continent rich in ethnic and population diversity, each with their own histories, languages, religions, phenotypes, and other characteristics, and this was equally true of descendants of Africans – and of Europeans, and of all other regions of the world, for that matter. America was no exception – and African Americans were among its rich diversity of ethnic groups. That is not to say that McCune Smith did not believe that there weren’t heritable traits that are characteristic of populations, and that African Americans did not tend to possess such traits. He observed that this was so, and regularly cited phenotypic and behavioral and emotional traits as examples – again, in peoples that had African ancestry as well as peoples that had ancestors from other places. But McCune Smith also observed that as populations moved, and mixed with other populations (a process he called “amalgamation”), and were influenced by climate and geography, their characteristics changed, giving rise to new ethnic groups and distinct populations as old ones disappeared. In short, there was nothing essential about race. McCune Smith’s theories on “race” – which he appeared to use more often to mean something more like “ethnicity” or “population” than the essentialist way it’s often used today – deeply influenced Frederick Douglass.[11]

How, you might ask, do I know for sure that this anonymous letter-writer was James McCune Smith? Well, there are many clues, some biographical. For one, the author wrote that he was “one of those free people of colour” that the ACS was purportedly created to help, and, more specifically, that he was “driven me to seek in this country those literary advantages with which the colleges of my own are teeming, but which are haughtily withheld from the free man of colour.” These were true of McCune Smith, but as far as I’ve been able to find, true of no one else in Glasgow at the time the letter was written. The author singled out ‘the beautiful Carolinas’ as a scene of rejoicing when and if slavery was abolished there; McCune Smith’s mother had been born into slavery in Charleston, South Carolina. The author also wrote in a style that closely matches McCune Smith’s known works, and employs quotes and phrases McCune Smith regularly used. Finally, as we have seen, the author expressed ideas that continued to be key themes in McCune Smith’s known writings.

The hunt for more McCune Smith contributions in Scottish and other non-American publications continues. Since he wrote that such contributions exist, they must – or at least, used to. Unfortunately, the full run of many Scottish newspapers, including the Glasgow Chronicle, do not appear to survive, or at least are very hard to find. This is also true of many British and other European newspapers, including the anti-slavery ones most likely to publish contributions by abolitionists such as McCune Smith. But you can be sure that I’ll keep digging, as long as it takes to find any that do survive, and as long as I can continue to find a way to do so.

[1] W. Innis Addison, ed., The Matriculation Albums of the University of Glasgow, From 1728 to 1858 (Glasgow: James Maclehose & Sons, 1913), 392.

[2] Philip A. Bell, ‘Death of Dr. Jas. McCune Smith’, The Elevator, 22 December 1865.

[3] ‘William Smeal [Obituary]’, in The Annual Monitor for 1878 or, Obituary of the Members of the Society of Friends in Great Britain and Ireland, for the Year 1877 (London/York, 1877), 150.

[4] ‘The University Anti-Slavery Petition’, Glasgow Chronicle, 22 February 1833, National Library of Scotland.

[5] U.K. Parliament, ‘Ministerial Plans for the Abolition of Slavery. (Hansard, 22 July 1833)’, accessed 9 January 2023, https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1833/jul/22/ministerial-plan-for-the-abolition-of#S3V0019P0_18330722_HOC_15.

[6] Amy M. Cools, ‘James McCune Smith and Glasgow: A Scholar’s Transatlantic Journey, 1821-1837’, Beniba Centre for Slavery Studies (blog), 17 October 2021, https://www.gla.ac.uk/research/az/slavery/news/headline_815417_en.html.

[7] James McCune Smith, ‘Extracts from Dr. Smith’s Journal [9-11 September 1832]’, The Colored American, 3 February 1838; James McCune Smith, ‘Dr. Smith’s Journal [Liverpool, 13-15 September 1832]’, The Colored American, 16 March 1839; James McCune Smith, ‘From Our New York Correspondent [February 1855]’, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, 16 February 1855.

[8] James McCune Smith, ‘To the Editor of the Glasgow Chronicle [15 January 1833]’, Glasgow Chronicle, 18 January 1833, National Library of Scotland.

[9] Amy M. Cools, ‘The Life and Work of Dr. James McCune Smith (1813-1865)’ (PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2021), 150, https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/38333.

[10] McCune Smith, ‘Journal [Liverpool, 13-15 September 1832]’. This extract is published in James McCune Smith, The Works of James McCune Smith: Black Intellectual and Abolitionist, ed. John Stauffer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 22–24.

[11] Cools, ‘Life and Work’, 256, 277–78, 293–301.

Great find! I only wish there was a photo of the middle part of the letter -- I wish I could read the full original text, in addition to the helpful context you provide.